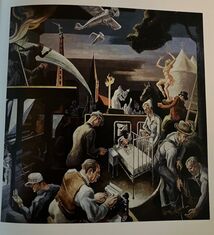

I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.

4 Comments

|

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed