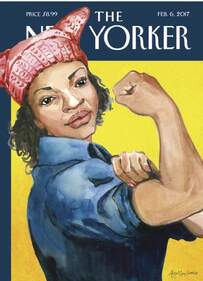

Slow briny sweat dripped into Sharon’s eye, determined and persistent. She wiped it away with the red faded bandana soggy from an afternoon of sweat and snot and stuffed it back into her equally sodden rear pocket. Behind her a tidy, curated garden unpocked with pioneering grasses and wandering upstarts. Before her, a browsy mass of mildewy coneflower and yellowing milkweed in a spiky undergrowth of orange cosmos being invaded by snow-on-the-mountain that was aquiver with honeybees, three different kinds of wasps, and who knows what kind of flies. Beyond that a vegetable garden with Italian zucchinis and purple-podded green beans that somehow grew from pinky finger size to giant overnight in the late summer humidity. As she took a step into the tangle, Sharon’s phone dinged: the half-hour alert for the evening abortion ban protest. But right there beside her foot was a young, enterprising poison ivy plant. She plucked a large violet leaf, folded it over, and wrapped it around the stem to block the urushiol oils from touching her and yanked out the plant. A risky maneuver, but it had worked before. A few steps beyond, a bristly patch of nut grass. She bent under the tall, floppy bee balm to pull out the long dangling rhizome roots, and then pruned the bee balm for another round of late flowering. Her phone dinged again. Now, only fifteen minutes to get downtown. Sharon took three giant steps out of the flower bed and ran to the mud room at the back of the house. She stripped off her bug-sprayed outfit and flew into the shower to soap off any chiggers that had wiggled through to bury into her tender parts like the sense of dissatisfaction that had sparked the women’s movement on suburban patios back in the 1960s. She shouldn’t have dawdled in the garden, now she is late. Prompt by habit, late isn’t a word that comes up in Sharon’s life often, and while she stepped into her jeans, it blossomed in her mind like a spot of period blood on a sanitary napkin. Late was a word of horror in her youth, in the days before she got birth control under control, before getting her tubes tied. Late terrorizes women for half their lives. The checking of the calendar, a paper calendar for her back then. How many days late? Am I late or did I skip? Hand tentatively hovering over the belly. Month in and month out. From the kitchen, the final alert dinged on Sharon’s phone. She shoved it in her bag and rushed to the garage. The tires on her bike needed air. She watched the gauge on the hand pump steadily climb to eighty pounds pressure, like the pressure that built up in those suburban women of old, before Roe v. Wade. As Betty Friedan put it in her book, The Feminine Mystique, it was a pressure, a strange stirring, a yearning arising from a long buried, unspoken problem: “Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’” Sharon didn’t read The Feminine Mystique when it came out; she was too young to notice it and her mother, who had worked her whole life, never mentioned it. In fact, Sharon hadn’t ever read the book until last month because for years she arrogantly considered herself the embodiment of feminism. First a braless, hippie chick who felt liberated enough to erroneously believe that she could align her periods with the phases of the moon for birth control. Even more so as a single mom who managed to pull off a decent career. But lately, with the whole feminism movement beating a retreat as the be-fruitful-and-multiply tradwives in aprons became the new radical counterculture, Sharon sensed her style of feminism was out of touch, even as an escort at Planned Parenthood and a member of NOW. The first hill into town was a ball-breaker. Sharon pointed her bike toward the rise and pedaled in low gear. Fast, then slow teetering at the top, finally growing steady and catching her breath in front of the green bungalow with the familiar Ruth Bader Ginsburg decal on the door. “Women belong in all places where decisions are being made,” read the decal next to an image of Ginsburg in her lace collar. Sharon threw Ginsburg a dirty look. The judge knew Roe v. Wade was headed for attack; she should have stepped aside early. She’d gambled with the rights of women and lost. Tomorrow, Indiana reinstates its abortion ban. Coasting down the hill, wind cooling her over-heated face, Sharon was furious that she had to leave her garden in a weedy mess for an abortion ban protest. Outraged that the rights won by those historically, histrionically, desperate women have been snatched away. The first of many rights in the shredder, perversely in the name of freedom. She sped up and coasted through a stop sign so she could get up the next hill. It’s not like women’s rights hadn’t been stolen before. She’d found the history, thanks to Professor Google and the New York Times archives. During WWII women had flooded into jobs and college slots. The Rosie Riveters that everyone knows about made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. But others held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. They filled the classes of universities. They were confident and independent. They made good money and had future careers. At the end of the war in September of 1945, all of that was stripped away and handed to returning soldiers in a false fear that the Great Depression would return. In just three months a million women were “freed” from their jobs. Soon it would be half of all working women. The rest took on grunt pink-collar jobs. Future doctors were recycled into high school biology teachers. The first-in-her-class Harvard grad Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. The wartime economic engine shifted gears and the Golden Age of Capitalism was ushered in by career housewives retrained to shop. It was a career of discontentment that left them feeling empty and invisible. A boxed-in brain-death boredom that beget a desperation so red hot that not even a martini with a twist could douse it. A desperation as broad and deep as the disenfranchisement that boosted Trump into the Oval Office and Sharon’s news feed. The Feminine Mystique sold three million copies in three years. Read in between making the Jello salad and folding the laundry, it roused women into following the lead of the civil rights movement, but often without women of color. They didn’t storm the Capitol, but they marched. They wrote books, started Ms. magazine. They ran for office, spurred equal pay and rights legislation. It’s because of them that all women can have credit cards and houses in their own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was because of these rabble-rousers that all women have access to birth control. And, for a brief shining moment, the right to end unwanted pregnancy. Then in 1981, things started tumbling backwards. Just as Paula Hawkins of Florida was the first woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate without following a husband or father in the job, and Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman on the Supreme Court, the idea that equality was a step down for women began to gain traction. And abortion rights became political bait. If the weather had been cooler and the hats hadn’t been dumped as racist and transphobic five years ago, Sharon might have worn her pink knit pussyhat from the Women’s March in D.C. at the beginning of Trump’s term. What an exhilarating day that was even if the new administration couldn’t care less. But it wasn’t useless. Like a good soaking rain stimulates growth in a garden, it stirred hundreds of women to run for office and tens of thousands to register to vote. The same ones that were voting for abortion rights state-by-state. Sadly, the sparsely right-to-choose gatherings on the courthouse lawn in little radical Bloomington and the ignored demonstrations at the Statehouse in Indianapolis never moved the needle in MAGA, cornfield-ruled Indiana that refused to put abortion on the ballot. But she went anyway. Sharon darted up an alley and onto the courthouse square. It was empty of protesters. Not even one waving a sign at passing cars. Locking her bike to the rack, she scanned the grounds for her friends and cocked her head to listen for protest chants, but there were none. She took the steps two at a time, toward the young organizer by the empty stage in the niggardly shade of a tall, skinny ginkgo tree. Sure the protest had taken off down the street without her, Sharon asked, “Which way did the march go? I need to catch up.” “March? There’s no march. It was a vigil.” “Vigil. That’s a hopeless perspective.” Sharon took off her bike helmet and shook out her hair. “Where is everyone?” “Gone.” “What do you mean, gone?” “You are late. Almost two hours.” The woman tapped her smartwatch. “That damned calendar app.” Sharon pulled out her phone and glared at it. “The time dial-ly thing is hard to use.” “I wondered where you were, hoped you weren’t sick or something. I know people texted you.” To Sharon’s chagrin, she saw a pile of texts from her protest friends. “Crap, I remember, I turned off text notifications. Got sick of texts sidetracking me and forgot to switch it back.” The woman gave her a poor-confused-old-lady look while brushing away an evening mosquito from her taut-skinned arm. Her phone buzzed. “I’ve got to take this; it’s a reporter from Indianapolis.” “Thanks for being here in time,” Sharon said as she turned away, longing for her days of unwandering focus. Of taut skin and thick hair. Days that felt like good change was in the air. This abortion thing made her want to move out of the state. But no matter where she might go, stifling attitudes toward women would go with her. They were woven into the culture, like racism. And for hard-working women of color, like the one following up with the reporter, it’s a double whammy. Suddenly thirsty for a stiff drink, Sharon jaywalked across the street, and found an empty solo seat at the bar crowded with young hipsters, many sporting tattoos on their firm skin and most with lots of thick hair including a couple of man buns and a braided beard. The bartender, busy performing a focused mixologist show—muddling, high arcs of pouring, over-the-head shaking—didn’t even glance Sharon’s way. She looked over the slim menu of craft cocktails with craftier prices, knowing that if she ever got the bartender’s attention she’d better be ready to order. Beyond her, with the studied look of a scientist, he measured dry gin, sweet vermouth, and Campari into a glass beaker of ice, stirred the brilliant red liquid with a long, twisted handled spoon, and strained it over a perfect square of ice in a round rocks glass. Sharon waved as he looked up after twisting a swath of orange peel into the classic Italian Negroni, miraculously catching his eye. She pointed at the drink and then to herself, nodding. He gave her a thumbs up. Negroni. One of those words that seemed like it is racial but isn’t. Like niggardly. Sharon looked around the bar. A white crowd. One that might be called privileged. Like her. Her Ancestry DNA test had shown she was Scottish through and through. She had hoped for a more diverse set of inputs, but it wasn’t to be. And her immigrant story is so old no one in her family remembers it. Born humbly, she never thought herself privileged until the woke movement awoke her to the simple enduring benefits of having pale skin, even wrinkled. The Negroni show encore was underway in front of her. The bartender measured and poured. He dramatically stirred, twisted, and placed the gorgeous ruby-red drink in front of her with a flirty flourish. She did her best eye-twinkle back and took a sip of the bitter cocktail. So appropriate for the day. On the TV hanging above the bar, news flashed of Trump’s lead in the polls and his likely indictment in Georgia for election meddling. And with it evidence of a new wave of feminism. The prosecuting district attorney with the lyrical Swahili name, Fani Taifa Willis, daughter of a Black Panther, taking on the biggest-baddest in front of the whole country. Sharon raised her glass to the steady-gazing prosecutor. “Here’s to you, Madam DA.” A few weeks ago, Sharon had been blown away by another woman with the mantle of a different power wrapped around her. The keynote speaker at the Bloomington Women’s History Month Luncheon, the resonating Manón Voice of Indianapolis, seemed made of the same passionate and poetic magnificence as Martin Luther King and Fred Hampton, but with a hip-hop sensibility. As the booze softened her brain, Sharon realized that women of color caught her eye more often than white women as they took their rightful place on the stage of the big world, the one beyond her fussy garden. They are fascinating. They stir her. She listens to Kamala Harris speeches. Takes the painful Smarter in Seconds lessons of Blair Imani on Instagram. Has Isabel Allende’s new novel, The Wind Knows My Name, on her bedstand. Loved Michelle Yeoh in Everything Everywhere All at Once. Inhales Amanda Gorman in each Vogue-y dress of the moment and has this stanza of her inaugural poem on the refrigerator: And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside She jostled her drink around the posh ice cube. Truth be told, she is a women-of-color groupie. But, after a lifetime of being surrounded by white, this influx of color is, well, colorful. What idiot wouldn’t be fascinated? But, she had read enough online to know that this, her riveted groupieness, is racist. That locked white eyes upon non-whiteness is an unwanted heavy weight for others to carry. Draining the last watered-down sip of the Negroni, she paid in cash with a small tip for the bartender—who never gave her a second look, or even a bill—and took her infinitely flawed and obviously unfascinating self home. *Rosie the Riveter reimagined as a woman of color, illustrated by artist Abigail Gray Swartz, graced the New Yorker February 6, 2017 issue, paying homage to the past, present and future of the feminist movement.

0 Comments

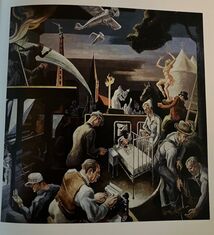

I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.  IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—Is this all?’” Today is the birthday of Betty Friedan, born in Peoria, Illinois (1921). Her thoughts, like the one above, put forth in 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, roused women into action for equality, challenging the widely shared belief that fulfillment had only one definition for American women: housewife-mother. Friedan was right about the depth and breadth of women's dissatisfaction. The book sold three million copies in three years. Women had been discouraged from working during the depression to give men jobs. But during WWII they flooded into jobs and college slots vacated by men gone to fight. They were independent. They made good money. They had future careers. They made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. They held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. But all that was lost upon the return of soldiers when the fear of another depression forced women out. It was promoted as the patriotic thing to do, but it decimated women’s lives as they were systematically relegated to pink-collar jobs in law, medicine and business or no jobs at all. Everybody knows how the brilliant Ruth Bader Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. But what I remember was my mother’s bitterness over being shunned by other women for working in our family flower shop. And the woman who married my stepfather after my mother died: she was forced out of medical school to make room for returning veterans and had to accept a career as a high school biology teacher when she wanted to be a doctor. But by the 1960s, the nearly psychotic and bored white women of the suburbs (yes, the same women courted by today’s politicians) tossed aside Tupperware, frozen dinners, and tranquilizers to put their racist, Bardot-draped, shoulders into righting the listing ship of women’s equality. They wrote books, marched in the streets, launched legislation, started magazines, ran for office. And strategically excluded women of color, just like the old suffrage days. That oft-scorned movement put women in congress, allowed us to have birth control pills and the right to terminate unwanted pregnancy, credit and houses in our own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was the second wave of feminism. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 stipulates that women receive the same pay as men for the same work. We're still working on that. And working on even allowing women to hold equal jobs. Stifling attitudes toward women are woven into our culture, like racism. And for women of color, it’s a double whammy. I have deeply pondered my own racism. From my late teens on, I did everything I could think of to reject racism. But recently, I was trashed on social media as a racist. At first, I protested. Not ME! But then I realized my trasher was right. I’m racist. I can’t help but be racist. And I have to own up to it because it helps me see my privilege, helps me understand the anger of those who look at me in disgust. This has led me to believe I am also riddled with bias against women, even though I am one. Even though I experienced decades of sexist slap-downs, forged radical non-Hollywood relationships with men, clawed my way as a single mother to fairly respectable positions, and pride myself on my feminist views. I can’t help it. It’s buried in me. Like racism, it’s part of my foundation. I was taught. By my family, my teachers, my bosses, my friends. By the lack of female authors, artists, scholars, or innovators available from which to learn. I can fool myself—like I did in the 1980’s, thinking I was no longer a racist because I forgot a Black friend’s color—that I’m not sexist because I have tried hard to unlearn what I was taught. It’s hard to excavate my biases. Almost impossible to see them. They lie hidden in my dark, irrepressible judgement of women who have chosen paths I deem inadequate—dissing Melania Trump’s plastic-surgery-modeling-rich-guy route when I should just try walking a mile in her ambitious, sky-high stilettos. They seep into my own language, that I must vigilantly correct—calling Joe Biden, Biden; but calling Kamala Harris, Kamala. Beyond me, out in the larger world, the third wave of feminism is blossoming. I Googled “feminist activists 2020,” and first up came a link to an October 2020 post on Mashable, “6 feminist activists to follow on social media.” Right away, I’m heartened. The women are all colors, shapes, sizes, ages, and religions. They are probably racist and sexist too, but I’m following them. Closely. And hoping, as this young woman points the way for us all: "...And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside..." --Amanda Gorman |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed