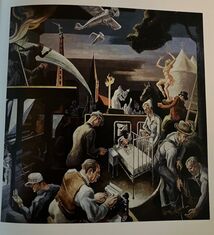

I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.

4 Comments

IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—Is this all?’” Today is the birthday of Betty Friedan, born in Peoria, Illinois (1921). Her thoughts, like the one above, put forth in 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, roused women into action for equality, challenging the widely shared belief that fulfillment had only one definition for American women: housewife-mother. Friedan was right about the depth and breadth of women's dissatisfaction. The book sold three million copies in three years. Women had been discouraged from working during the depression to give men jobs. But during WWII they flooded into jobs and college slots vacated by men gone to fight. They were independent. They made good money. They had future careers. They made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. They held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. But all that was lost upon the return of soldiers when the fear of another depression forced women out. It was promoted as the patriotic thing to do, but it decimated women’s lives as they were systematically relegated to pink-collar jobs in law, medicine and business or no jobs at all. Everybody knows how the brilliant Ruth Bader Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. But what I remember was my mother’s bitterness over being shunned by other women for working in our family flower shop. And the woman who married my stepfather after my mother died: she was forced out of medical school to make room for returning veterans and had to accept a career as a high school biology teacher when she wanted to be a doctor. But by the 1960s, the nearly psychotic and bored white women of the suburbs (yes, the same women courted by today’s politicians) tossed aside Tupperware, frozen dinners, and tranquilizers to put their racist, Bardot-draped, shoulders into righting the listing ship of women’s equality. They wrote books, marched in the streets, launched legislation, started magazines, ran for office. And strategically excluded women of color, just like the old suffrage days. That oft-scorned movement put women in congress, allowed us to have birth control pills and the right to terminate unwanted pregnancy, credit and houses in our own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was the second wave of feminism. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 stipulates that women receive the same pay as men for the same work. We're still working on that. And working on even allowing women to hold equal jobs. Stifling attitudes toward women are woven into our culture, like racism. And for women of color, it’s a double whammy. I have deeply pondered my own racism. From my late teens on, I did everything I could think of to reject racism. But recently, I was trashed on social media as a racist. At first, I protested. Not ME! But then I realized my trasher was right. I’m racist. I can’t help but be racist. And I have to own up to it because it helps me see my privilege, helps me understand the anger of those who look at me in disgust. This has led me to believe I am also riddled with bias against women, even though I am one. Even though I experienced decades of sexist slap-downs, forged radical non-Hollywood relationships with men, clawed my way as a single mother to fairly respectable positions, and pride myself on my feminist views. I can’t help it. It’s buried in me. Like racism, it’s part of my foundation. I was taught. By my family, my teachers, my bosses, my friends. By the lack of female authors, artists, scholars, or innovators available from which to learn. I can fool myself—like I did in the 1980’s, thinking I was no longer a racist because I forgot a Black friend’s color—that I’m not sexist because I have tried hard to unlearn what I was taught. It’s hard to excavate my biases. Almost impossible to see them. They lie hidden in my dark, irrepressible judgement of women who have chosen paths I deem inadequate—dissing Melania Trump’s plastic-surgery-modeling-rich-guy route when I should just try walking a mile in her ambitious, sky-high stilettos. They seep into my own language, that I must vigilantly correct—calling Joe Biden, Biden; but calling Kamala Harris, Kamala. Beyond me, out in the larger world, the third wave of feminism is blossoming. I Googled “feminist activists 2020,” and first up came a link to an October 2020 post on Mashable, “6 feminist activists to follow on social media.” Right away, I’m heartened. The women are all colors, shapes, sizes, ages, and religions. They are probably racist and sexist too, but I’m following them. Closely. And hoping, as this young woman points the way for us all: "...And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside..." --Amanda Gorman  People whine, or more modernly "whinge," about new words. About the new ways of using old words. They want to nail down English, make it hold still. Like a dead language, like Latin. But English is alive, recklessly sprouting new words for old things, new words that meant old things but with a new twist, old words used new ways, and new words for new things. I used to be deep in the whirlpool of new words, so close that I was one with it. I was plugged-in when plugged-in was added to the dictionary. A new word would appear in my mind seamlessly as it shot across the tongues of my friends and the pages of books and newspapers. Far out. Fab. Groovy. Outta sight. Righteous. Bummer. Gimmie some skin. Hang loose. Ecosystems. Whole systems. Spaceship Earth. Zero population. Wild edibles. Amerika. Dig it. Later, I was there in my little suit and scarf when Materiel Management booted out the Purchasing Department and Human Resources took over the Personnel Office. I ran spritely beside adware, subfolder, brain dump, microbrew, the n-word, and biodiversity. I was hot when chill out was a thing. But somehow, slowly, almost imperceptibly, some words started outpacing me. A new word for stealing, “gank,” (as in “you ganked my X-Box”) came and went without me. Polyamorous slipped by me unnoticed but woo-woo didn’t. Then one day I was shocked to discover that garden ecosystems were old hat, replaced by the swankier permaculture. Gen Xer’s had axed that old-school talk and broadened the idea. By renaming it, they claimed the concept, took it away from the hippies-turned-Boomers. I resisted. I didn’t want to use that new, pretentious word. Then I realized this is how a person grows old. One step at a time out of sync as the words dance and mutate until they have all rushed ahead and left you behind with a curly old lady perm and frumpy clothes. No longer yogurt, sourdough, and sauerkraut; it’s wild fermentation. It’s not you are what you eat, it’s the microbiome. New and redefined words swirl up like mosquitoes on a hot summer night from the internet, the news, movies, and conversations. Has it always been this fast? Have words always been this fleet-footed but we didn’t know how to measure? “Are you going to temp that?” The Oxford English Dictionary (which keeps track of a thousand years of English and some 600,000 current and obsolete words) has added more than 4,000 new words since the beginning of 2019. And I think they are behind. I know I am. It took me forever to fully understand the ridiculously simple word, “meme.” And “litigate” challenges me as it populates the news, mirroring the contentiousness of our society, as in this sentence from the New York Times: “Racism is litigated over and over again when another video depicting another atrocity comes to light.” Litigate in my mind has always meant to decide in a court of law. But now its archaic meaning, to dispute, has been re-embraced. Who started that? Bitchface. Clapback. Nothingburger. Shade. Throwing shade. Meme. Tropes. Dog whistle. Salty. Troll. Dox. The singular They. Woke. Lynching. White fragility. Infodemic. Hashtag. They rush toward me, not just as new words but as signs of seismic changes. The world shifting beneath me like the proverbial quicksand from which Lassie had to rescue Timmy on television back in my childhood.  My mind is full. That’s why I can’t get around to revising my book manuscript. Every time a little space opens I stuff it with something new. Scan the minutes of the last Historic Preservation Commission and consider going to meetings. Brush up on my French, or learn Spanish beyond the most rudimentary level. Mend a sheet. Change my mind about saturated fats. Go to Athens and Istanbul. Have a cold and binge watch a Turkish soap opera. Wash and paint the front porch. Read one or three of the gazillion books stacked around the house and the National Geographics and New Yorkers too. Make garden revisions. Write a letter to city council members about granny flats. Get my bike going and take long rides. Go to the movies. Make mayonnaise. Plan next year's trip to Paris. Write a blog post. Anything but revise the manuscript. It sits in a sturdy faux leather ring binder I bought on eBay years ago. All 82,782 words spread over 331 pages that have, according to Word, already been edited 232 hours and 34 minutes (and this is a second draft, so add to that the 122 hours and 33 minutes of the first draft). But I'm whining. That's only some 44 days of full-time work. I tell myself that when the weather gets really hot then I will be able to sit in my chair in my air conditioned office for the long hours required to get this material up to snuff. Butt In Chair. But the truth is, I’m in a rocky relationship with this book. Foremost, I love it passionately and that causes all kinds of problems. I never loved Leave the Dogs at Home, so I could brutally beat it up, slice and dice it, no problem. But because I love this book, it scares me. I worry that my beloved is no good. That my affections are ill spent. What if I open it again, and it is terrible? And, unlike Leave the Dogs, this book, tentatively and poorly named Counter Groove, isn’t finding its own way yet through the world of publishing. Leave the Dogs, even in its worst, most discombobulated state, was loved. It attracted mentors and grants. I had to run to keep up with it. The Dogs had a destiny from the get-go. So far, this work is searching for its path. Still, it took five years of revisions for The Dogs to get there. And I can remember that agony, that madness. Do I want to succumb? Blot out almost everything else and submerge myself? Is there any other way to do it? Earlier this week, I was thinking about getting a cat. My last two cats have lived about 20 years. If I live 20 years to age 88, I will have outlived generations of women in my family who have all expired between the ages of 83 and 86. Would the poor cat find herself ancient and alone? Some say I’m healthier and will live longer. My annuity company doesn't think so. Online longevity calculators put me at 95. But they don't know about my long-gone rotten appendix and gall bladder. The nasty DCIS cells dug out and radiated last year. All this longevity thinking led me to the familiar zone of pondering how I’m spending my ever-dwindling time and my ever degenerating memory. Twenty years is 7,305 days. What's 44 days? Less than 1%. The thick binder of pages must be opened. The pencil must get busy. The revision must begin. the papers must be stuck on the wall. The madness must be welcomed. I cannot abandon my beloved because I’m afraid it won’t get a lift under its wings. I have to open the windows and doors, let the wind in.  It was early in the evening on a day that had been a little off-kilter when I saw her coming down the sidewalk of downtown Lexington, Kentucky. It was an overnight step on my way to Virginia for the little May book tour. I’d always wanted to explore the city, so I booked a pricey room at an old inn since I was indulging myself before an unwanted surgery that I would have at the end of the tour. On the way down through Southern Indiana on SR 37, a two lane road that wound through fields of golden ragwort and miniature towns, I begin to fret over my haircut. Obsess really. A fairly new cut for me. It’s asymmetrical and loosely based on the haircut of Claire Underwood, a ruthless strategist on the Netflix series House of Cards. I’d tried wearing my hair long, up in buns and French twists, but it’s too thin and the style made me look like an old lady (which, of course, I am). I wanted something more modern, more radical. Something that rocked. And this haircut did. I even had blue streaks in it. But I blew the follow up trim (it can be hard to replicate the original cut, easy to lose that je ne sais quoi of the new cut). I’d been late to the appointment. So my stylist was rushed. She asked me how long in the back. I told her to just do whatever. I should have said short. It was frumpy and too long in the back. I wanted to look as good as an old lady could for the book tour. So when I got to Lexington, I Google Mapped for the hair salon closest to the inn and lucked into a stylist in between appointments to get the back cut short, short, short! Don’t touch the sides or front, don’t use hair thinning shears or razors; I want a good scissor cut. I showed her photos of Claire Underwood’s hair cut pulled up online on my phone. And I got want I wanted. But the rest of the day I couldn’t quite get my way. My room at the inn felt very tired, the furniture not antique but just cheap, beat, old stuff, the carpet looked like it was from the 90s, and the bedspread was one of those awful things that you don’t even what to touch but have to take it off and put it in the corner. The inn had a restaurant but it seemed pretentious yet uncomfortable, the fatty food expensive. I wandered the few blocks to downtown Lexington. I stopped at a brew pub, sat in a black padded swivel chair at a long bar facing a brick wall with oversized posters. The music was loud. Several minutes went by without a bartender even glancing my way, despite my hip haircut with the short short back. So I left. I walked and walked and walked, harassed over and over by the same drunk panhandler. Nothing looked good. I ended up at another little brew pub close the inn. Had a local beer, some bar food, and an odd, depressing conversation with man who sold furnishings to universities about his iron sculpture business that failed even though celebrities had purchased his work. Before turning in for the evening the next day's drive to Lexington, Virginia, I began to think about my breakfast. I’m picky about breakfast. I don’t need a lot, but I want a healthy one. Yogurt with fresh fruit is nice. The inn’s restaurant offered a yogurt on their breakfast menu for 10 dollars. Nope. That won’t do. So I walked a few blocks to a little store on Short Street called Shorty’s and bought a little container of semi-fake, fruity yogurt, a banana, and a bag of local granola. And this is when I saw her. On the way back to the inn. Walking toward me. She had this dramatic, kick-ass asymmetrical haircut and was wearing a white t-shirt printed with a large black “United.” She looked at me as the distance between us shortened and smiled nervously. I was focused on her hair cut and how cool she looked. She had a rebellious but not callous vibe; somewhere in her 20s I guessed. I smiled back. When we grew even on the sidewalk, she stopped to speak to me. That’s when I saw that the shaved side of her head wasn’t a cool, rebel cut. It had a heartbreaking arc of metal surgical staples that must have spanned four inches. She asked me if I could help her. She explained that she’d just had brain surgery. Well, that sure was obvious. I recognized those staples from Jim’s brain surgery, the one he had when his lung cancer spread there, just a few months before he died. She showed me a catheter port on the taped to back of her hand and told me she was doing cycles of both chemo and radiation. She was so tired, and it was hard to think clearly. She was forgetting stuff. And for some reason her credit card didn’t work at the gas station, and she was out of gas. So she had left her car at the station and started walking to see if she could beg some cash for gas. There weren’t many people on the sidewalk and so far, all that had happened was that some guy had cussed her out. This was no drunk panhandler. She looked completely fatigued, so so weary. I asked her to sit down on some nearby steps with me. She’d had seizures at work, that’s how they’d discovered the cancer. And she was trying to keep her job, but it was hard. They’d taken out a chuck of her brain about the size of fist. And there was still more cancer in her brain that was harder remove. If the chemo and radiation didn’t work, then they would do a second operation. The size of a fist. That’s what my oncology surgeon had told me. I had abnormal cells in my left breast that were the size of a fist. Is this taught in medical school? How to describe the size of tumors. Big as a thumb. As a fist. What would be bigger? A foot? I almost never carry much cash. But because I was traveling, I had some. I pulled out my wallet and handed her a twenty. She looked down, paused, and then said. “It’ll take 35 to fill up the tank. Maybe by the time I need gas again I’ll have figured out what’s wrong with my credit card.” I gave her another twenty. And I told her about my breast fist. Beyond my closest friends and family, she was the first person I’d told. And about Jim’s cancer. And we talked for quite a while about how things just come from nowhere. She wanted to pay me back, send me a check. I told her no. Then she asked if she could give it my church. I told her to just help someone else when they need it. She stood to walk back in the direction she had come. “Live each day as it comes,” she said me before she left. “I’m keeping you in my prayers.” I can’t get her out of my mind. Every time I think about my hair cut now, I see her instead of the merciless Claire Underwood. And I feel lucky. My fist, once removed, turned out to only have a section of bad cells in the size of a tiny fingernail, as described by my surgeon as she held out her small Asian pinkie finger. Low-risk pre-cancer. I don’t need radiation. No chemo. Even though today my chest looks like a gruesome patchwork quilt, it will heal. But I bet this young woman won’t be as lucky.  Virginia always takes me by surprise. I’ll be rearranging my NetFlix queue or doing some other essential but non-essential thing - cooking, dusting, or paying bills - and a green flash of Virginia darts in. The blue, hazy vistas. The open high mountain pastures. Fat yellow, black and white striped monarch butterfly caterpillars munching on milk weed. White two-story farmhouses with green roofs and wrap-around porches. The images elbow each other for room in my mind. I stop, pull back from whatever I'm doing, and let it all flow over me. I invite in those ancient folded Appalachian ridges that stretch from Newfoundland to Alabama and pull up little slices of Virginia luck. Pale pink spring cherry blossom petals blanketing the ground, up to my ankles. A sign in the window of the H&H Cash Store in Monterey, next to a poster for maple syrup and buckwheat flour: If we don’t have it, you don’t need it. The August heat hammering down any thought of moving quickly. Thousands of Arbogasts in the wide Shenandoah Valley and the steeps and flats of Highland County. Tiny Willie’s Pit BBQ hole-in-the-wall BBQ in Staunton that’s not there anymore.

And then, a few days later on Tuesday, April 26 at 7 p.m., after I have checked in and found my long-lusted-after seat in a rocking chair on the second story porch at the Highland Inn in Monterey, high up in the "little Switzerland" of Virginia, I am lucky enough to do a reading at the public library. It was in Highland County that I began to understand that in the debris of Jim’s death was a remarkable gift, really a rare chance to remake myself --the core of Leave the Dogs at Home’s story: Here's an excerpt: White picket fences announced McDowell, which was really just a few houses along the road. It was easy to find the old house—it was the only brick house in town. It was a Hull family house built in the 1800s that had served as a Stonewall Jackson headquarters, a Civil War hospital, a hotel, a stagecoach stop, and now a museum. I left the girls in the Element under a lone tree several blocks away, every possible window open, water dish filled to the brim, and calculated I had an hour before the sun moved from behind the tree to beat down on them. A stray breeze moved through the thick air. Maybe it was slightly less hot here. My elderly cousin was waiting for me upstairs at a heavy wooden table in a room lined with genealogy books. The slight scent of mildew tickled my nose. An air conditioner cranked noisily in the window. My shorts and T-shirt seemed disrespectful next to his white pressed shirt and brown suit and tie. He listened to me recite my lineage, nodding his head at each generation. Elizabeth and Michael. Elisabeth and David. Katherine and Enos. Isabele and Sanford. Cordelia and Enos. Pearl and Straud. Maxine and Elmore. “Yes, I know your family,” he said. “And I know where the old house is.” I unfolded a map and scooted it across to him. He ran his thin, smooth fingers over the web of back roads. “The old house is here,” he said, tapping at the map with his index finger. “In the field behind a newer house. As you drive around this curve you can just see it. It’s before the road turns to gravel and goes up the mountain. It was in Arbogast hands until a few years ago, but they had to sell.” Three hours later I pulled the truck over onto a small grassy shoulder in the curve of road next to a flock of sheep, the dogs whining to chase the herd. I thought this spot might be where my cousin had pointed to on the map. There was an old house set back far away. I couldn’t really see. The air undulated in the broiling sun. And then it hit me. It didn’t matter if this was the house or not. What mattered was how Michael had broken free from the restraints and traditions of the old ways to find a new way in a new land. He had left the old wars and took on new ones. While others cried and whined over being duped by the Soul Traders, he served his time and made his dream happen. Who knows what misery and horror he might have seen, being the only survivor of his German family, who may have been wasted by typhoid fever or mowed down in war. But Michael built a better life on the disaster of their deaths. As surely as he mourned them, he lived proudly and made Arbogast a name that rings with honor across the Shenandoah Valley. My Jim and career disasters seemed so shallow in comparison and my bleak grief over the loss of the former me so indulgent. But one thing was for sure: my life was getting better. I wasn’t headed for just a different life, but a better one and a better me. One that would not be here if Jim were alive. And it was time to be grateful and unabashed about living it. This is verboten thinking. Widows and left-behind lovers are never supposed to say this. We’re supposed to say that our relationships and marriages were perfect. You were crazy in love. It’s like half of you is gone, He was everything to me. Once your main squeeze kicks the bucket, the union, no matter how complicated or imperfect, becomes sacrosanct. The dead one golden and wonderful, the one left behind without a reason to go on. All the bad times must fall away, and only the good times can remain. We are allowed to stumble onward, bravely. We are allowed to heal and learn to enjoy life again. We are allowed to love again. But we are not supposed admit that life is better after a lover’s death. I needed to write about this, but I didn’t want to. People would think it was cathartic, therapy writing, a cleansing. A way for me to process my emotions. But I was doing just fine processing. I didn’t even think I was forging new ground. All I was doing was walking a path walked by many but unspoken of, and these important things needed to be said out loud. It’s not that I was glad that Jim was dead, but he was. And because of the chaos of his death I had a chance to break out of my crystallized and hardened patterns of predictability, to crack the calcified static of my life. In the rubble of Jim’s illness and death, I had a chance to walk into the next stage of my life with a new perspective. Some people never have, or take, this chance; instead they become frozen into who they are, what they think, how they act.”  Winter is slipping away, and it hasn’t even really started yet. I can feel it. Before you know it, those daffodils will be popping up and courting me, calling me outside, and I will not be ready. I love winter. But not why you might think. Yes, the raspberry canes turn purple, and the browns and grays of the landscape are as subtle and layered as a finely turned Stanley Kunitz poem. Yes, the sharp clarity of air inhaled clears the viruses and muck of summer from my brain. Yes, the night stars are as crisp as jewels in the dark sky. Yes the flannel sheets are cozy, the wood fires are toasty, and the stews are satisfyingly tribal. But it's the interiors of winter that I love. That's where the warm and broad luscious world of words lives. Cold, sleet, ice, dreary? I never really notice once I let myself go. And I always want to let go before I can. The yearn for an unbroken fall forward into all the words I can’t get to when I’m digging in the garden or putting up jars of lime blueberry jam is palpable. It's an impossible situation. I can never get to all the words in any winter (they are so short!) and each winter's already too big allotment of words always expands beyond all expectations as ideas spring off into wild directions, so every spring starts with me undone. Over the summer, words pile up - books unread, New Yorkers and Harper's stuffed and stacked in corners, articles bookmarked in my browser. The descent into words isn't just a day or two here and there. Not just a few hours. It's a whole indulgent, obsessive, unaware-of-the-world-around-me stretch that is never long enough. I’m mid-fall right now, a free, wide-armed collapse into the ideas of others and the notions that burst out of my fingers dancing in response across the keyboard. But I stay in mid-fall for so long. Not really totally immersed, and it pains me. Already November has evaporated. Okay, it was a very mild November, and I was outside. But today was a chilly December 1. And even though it was a disciplined day with some decent progress on my novel and a couple lovely and brain shifting dips into the worlds of Edward O. Wilson and Alexander James Thom, and some good reading over lunch, the day was still taken by half with the clamor of practicalities. Bake bread . . . do yoga . . . finish finances and put away papers . . . record movies for Cabo vacation . . . make plans to go the art bazaar at the UU church on Friday . . . empty the dishwasher . . . And I can see more coming right at me. A swelling barrel-wave of fall stoppers: the making of truffles to send off in Christmas packages, trips to the post office, not the mention the holiday jerky and cherry chocolates or the wrapping of presents and general partying. Things I love. So, I can never quite complete the immersive fall that I need - the time when no chores or complicated recipes or Facebook scanning are of any interest, and everywhere are only the cascades and eddies of words and the explosions of ideas - until after the New Year. And then I’ve only got about two months (taking a week off to laze on the beach in Cabo) to do what is really a year’s worth of study and writing before the light starts to change and those damned crocus nod their lovely heads. Tomorrow the balance will shift; it has to, because winter is almost over already.  I’ve been a really good girl this week. It might seem boring to you, but holy cow! look at what I got done: ~The new book manuscript has expanded by 20 or so pages. ~I have reduced myself by about 4 pounds by simply not overeating. ~A few items have been crossed off my to-do list. New insurance for house and car. New drug plan I hopefully will never use for Medicare. Scheduled my "Welcome to Medicare" preventive visit for January. ~A big section of my tightly packed storage closet under the stairs was opened up when I realized that I may never go camping again and gave all my gear to my daughter. ~I managed to visit a book club that had read Leave the Dogs at Home and not make a fool of myself. ~To help me keep my character Connie in my new manuscript in context, I read a 1969 issue of Zap Comix, the little red Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung book, and big chucks of books and articles about the Weatherman bombings in the 1970s. AND I joyfully did a little off-topic reading in the rolling and unrolling essays in The Faraway Nearby by Rebecca Solnit - book I’ve been meaning to read for over a year. ~I dedicated a few hours each day to promoting Leave the Dogs at Home and prodding others to chat it up. ~I’ve maintained a healthy balance between sit-your-butt-in-the chair focus and get-your-butt-moving walks, leaf-sweeping, and bicycle riding. I haven’t eaten too much chocolate or had too much beer or tipped back more than one glass of wine in the evening. I’ve kept a happy balance between bread, meat and veggies. ~I figured out how to make my computer quit misbehaving, again. ~I finally wrote a blog post. True, not everything is perfect. There is a stack of Paris books and artifacts on the upstairs couch that’s been there over a month. Recipes, magazines, and who knows what are scattered on the dining room table and kitchen counters that really need to be scrubbed down. And, my desk. It's a hot mess. Out overall, it feels wonderful. This structured life is good for me. My brain is charged and sparky. My gut is less gassy and burny. And Shit is gettin' done. But that fringe of mess around the house? That's a rebellion brewing in the alleyways of my being. A small collection of cells who want to just go screw around. They’ve started protesting. Marching the back streets with signs held high and chanting, “Hell no we won’t go.” If I ignore the rebels they will come with pitchforks and sharpened hoes to break down the static structure of my days. Blockade the progress of the new book with day dreaming. Sabotage my balanced diet by gobbling the stacks of cookies I take to my book events. So this is my secret plan: Give in, just a little. Let the rebels run freely, maybe for a whole day, wear them out so they will go sleep like dogs after a day of romping in the woods. Because without them, without their wild, dynamic chaos, the clamp of structure would closes everything down, and I would have to abandon all for complete rebellion.  Eating ice cream on Daddy's birthday, a family tradition of oh so long ago! Eating ice cream on Daddy's birthday, a family tradition of oh so long ago! Tuesday was Arbogast feast day. I was so busy, I forgot to celebrate. I almost always forget. You'd think I'd remember, because the 21st is also my father's birthday, a memory rich with vats of homemade ice cream and plates heavy with thick-sliced tomatoes. oh well. Instead I will give a nod to my 5th great grandfather, Michael who, with his wife Elizabeth, started up the Arbogast clan that arose from Virginia. Michael immigrated from Cologne, Germany where he was born in 1734. He arrived on the Speedwell in Philadelphia at age 17, parents and siblings all dead, and threaded his way through the big mountains west of the Shenandoah Valley to Highland County in 1758. These days, Arbogast is known as a "good valley name" and the graveyards are full of Arbogast tombstones, unlike Indiana. Immigrants from Germany, England and Ireland (plus a few folks wooed from Pennsylvania) were the ones who felled the trees in Virginia to made way for the farms, and to pay off their passage. He was naturalized in 1770, patented 130 acres there in 1773 and added more acreage over the years. He married a natural born Virginian and fathered two rarely noted daughters and seven oft-noted sons (several of whom served in the American Revolution). He died at age 79. In his will, he left his wife "one-third possession of at the time of my decease for and during her natural life time and her to keep possession of the dwelling house where in I live during the said period of her life and the adjoining to said house and all the under of following articles: to-wit, her bed and furniture, one pot, one baskin, one dish, two plates, two spoons, one fleish fork, one laddle, one kettle, one coffee pot, two teacups and saucers, one set of knives and forks, lisc (?) tin cups, two chairs, one large chest, one spinning wheel, one wool wheel, one pair wool cards, one pair cotton cards, the table in the house, all her books, her saddle and bridle, one tin bucket, three coolers for milk, two head sheep, two of my best milk cows, one horse creature, of not less value than fifteen pounds currant money, all her clothes, and the mulatto girl named Nancy." I hope things worked out okay for Nancy. My 4th great grandfather, David Arbogast. and his brother Michael, and "their heirs from them" were excluded. Maybe they had already received their shares when emigrating on to the east, or maybe there just wasn't enough room in Virginia for all of those big Arbogast personalities. Michael moved over the mountain to establish Arbovale, now part of West Virginia. David moved to Indiana, leaving his twin brother behind. David, who with his wife Elizabeth had five sons and four daughters, died at 109 years of age in Andersonville, in Posey Township - about two hours away in the northwest corner of Franklin County. Originally known as Ceylon, was laid out in 1837 by Fletcher Tevis, and renamed in 1849 after Thomas Anderson, a tavern owner. David was living in Virginia when he was 49, and it looks like all the kids moved with him, so the next 50 years surely were interesting. |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed