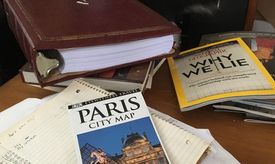

My mind is full. That’s why I can’t get around to revising my book manuscript. Every time a little space opens I stuff it with something new. Scan the minutes of the last Historic Preservation Commission and consider going to meetings. Brush up on my French, or learn Spanish beyond the most rudimentary level. Mend a sheet. Change my mind about saturated fats. Go to Athens and Istanbul. Have a cold and binge watch a Turkish soap opera. Wash and paint the front porch. Read one or three of the gazillion books stacked around the house and the National Geographics and New Yorkers too. Make garden revisions. Write a letter to city council members about granny flats. Get my bike going and take long rides. Go to the movies. Make mayonnaise. Plan next year's trip to Paris. Write a blog post. Anything but revise the manuscript. It sits in a sturdy faux leather ring binder I bought on eBay years ago. All 82,782 words spread over 331 pages that have, according to Word, already been edited 232 hours and 34 minutes (and this is a second draft, so add to that the 122 hours and 33 minutes of the first draft). But I'm whining. That's only some 44 days of full-time work. I tell myself that when the weather gets really hot then I will be able to sit in my chair in my air conditioned office for the long hours required to get this material up to snuff. Butt In Chair. But the truth is, I’m in a rocky relationship with this book. Foremost, I love it passionately and that causes all kinds of problems. I never loved Leave the Dogs at Home, so I could brutally beat it up, slice and dice it, no problem. But because I love this book, it scares me. I worry that my beloved is no good. That my affections are ill spent. What if I open it again, and it is terrible? And, unlike Leave the Dogs, this book, tentatively and poorly named Counter Groove, isn’t finding its own way yet through the world of publishing. Leave the Dogs, even in its worst, most discombobulated state, was loved. It attracted mentors and grants. I had to run to keep up with it. The Dogs had a destiny from the get-go. So far, this work is searching for its path. Still, it took five years of revisions for The Dogs to get there. And I can remember that agony, that madness. Do I want to succumb? Blot out almost everything else and submerge myself? Is there any other way to do it? Earlier this week, I was thinking about getting a cat. My last two cats have lived about 20 years. If I live 20 years to age 88, I will have outlived generations of women in my family who have all expired between the ages of 83 and 86. Would the poor cat find herself ancient and alone? Some say I’m healthier and will live longer. My annuity company doesn't think so. Online longevity calculators put me at 95. But they don't know about my long-gone rotten appendix and gall bladder. The nasty DCIS cells dug out and radiated last year. All this longevity thinking led me to the familiar zone of pondering how I’m spending my ever-dwindling time and my ever degenerating memory. Twenty years is 7,305 days. What's 44 days? Less than 1%. The thick binder of pages must be opened. The pencil must get busy. The revision must begin. the papers must be stuck on the wall. The madness must be welcomed. I cannot abandon my beloved because I’m afraid it won’t get a lift under its wings. I have to open the windows and doors, let the wind in.

6 Comments

Virginia always takes me by surprise. I’ll be rearranging my NetFlix queue or doing some other essential but non-essential thing - cooking, dusting, or paying bills - and a green flash of Virginia darts in. The blue, hazy vistas. The open high mountain pastures. Fat yellow, black and white striped monarch butterfly caterpillars munching on milk weed. White two-story farmhouses with green roofs and wrap-around porches. The images elbow each other for room in my mind. I stop, pull back from whatever I'm doing, and let it all flow over me. I invite in those ancient folded Appalachian ridges that stretch from Newfoundland to Alabama and pull up little slices of Virginia luck. Pale pink spring cherry blossom petals blanketing the ground, up to my ankles. A sign in the window of the H&H Cash Store in Monterey, next to a poster for maple syrup and buckwheat flour: If we don’t have it, you don’t need it. The August heat hammering down any thought of moving quickly. Thousands of Arbogasts in the wide Shenandoah Valley and the steeps and flats of Highland County. Tiny Willie’s Pit BBQ hole-in-the-wall BBQ in Staunton that’s not there anymore.

And then, a few days later on Tuesday, April 26 at 7 p.m., after I have checked in and found my long-lusted-after seat in a rocking chair on the second story porch at the Highland Inn in Monterey, high up in the "little Switzerland" of Virginia, I am lucky enough to do a reading at the public library. It was in Highland County that I began to understand that in the debris of Jim’s death was a remarkable gift, really a rare chance to remake myself --the core of Leave the Dogs at Home’s story: Here's an excerpt: White picket fences announced McDowell, which was really just a few houses along the road. It was easy to find the old house—it was the only brick house in town. It was a Hull family house built in the 1800s that had served as a Stonewall Jackson headquarters, a Civil War hospital, a hotel, a stagecoach stop, and now a museum. I left the girls in the Element under a lone tree several blocks away, every possible window open, water dish filled to the brim, and calculated I had an hour before the sun moved from behind the tree to beat down on them. A stray breeze moved through the thick air. Maybe it was slightly less hot here. My elderly cousin was waiting for me upstairs at a heavy wooden table in a room lined with genealogy books. The slight scent of mildew tickled my nose. An air conditioner cranked noisily in the window. My shorts and T-shirt seemed disrespectful next to his white pressed shirt and brown suit and tie. He listened to me recite my lineage, nodding his head at each generation. Elizabeth and Michael. Elisabeth and David. Katherine and Enos. Isabele and Sanford. Cordelia and Enos. Pearl and Straud. Maxine and Elmore. “Yes, I know your family,” he said. “And I know where the old house is.” I unfolded a map and scooted it across to him. He ran his thin, smooth fingers over the web of back roads. “The old house is here,” he said, tapping at the map with his index finger. “In the field behind a newer house. As you drive around this curve you can just see it. It’s before the road turns to gravel and goes up the mountain. It was in Arbogast hands until a few years ago, but they had to sell.” Three hours later I pulled the truck over onto a small grassy shoulder in the curve of road next to a flock of sheep, the dogs whining to chase the herd. I thought this spot might be where my cousin had pointed to on the map. There was an old house set back far away. I couldn’t really see. The air undulated in the broiling sun. And then it hit me. It didn’t matter if this was the house or not. What mattered was how Michael had broken free from the restraints and traditions of the old ways to find a new way in a new land. He had left the old wars and took on new ones. While others cried and whined over being duped by the Soul Traders, he served his time and made his dream happen. Who knows what misery and horror he might have seen, being the only survivor of his German family, who may have been wasted by typhoid fever or mowed down in war. But Michael built a better life on the disaster of their deaths. As surely as he mourned them, he lived proudly and made Arbogast a name that rings with honor across the Shenandoah Valley. My Jim and career disasters seemed so shallow in comparison and my bleak grief over the loss of the former me so indulgent. But one thing was for sure: my life was getting better. I wasn’t headed for just a different life, but a better one and a better me. One that would not be here if Jim were alive. And it was time to be grateful and unabashed about living it. This is verboten thinking. Widows and left-behind lovers are never supposed to say this. We’re supposed to say that our relationships and marriages were perfect. You were crazy in love. It’s like half of you is gone, He was everything to me. Once your main squeeze kicks the bucket, the union, no matter how complicated or imperfect, becomes sacrosanct. The dead one golden and wonderful, the one left behind without a reason to go on. All the bad times must fall away, and only the good times can remain. We are allowed to stumble onward, bravely. We are allowed to heal and learn to enjoy life again. We are allowed to love again. But we are not supposed admit that life is better after a lover’s death. I needed to write about this, but I didn’t want to. People would think it was cathartic, therapy writing, a cleansing. A way for me to process my emotions. But I was doing just fine processing. I didn’t even think I was forging new ground. All I was doing was walking a path walked by many but unspoken of, and these important things needed to be said out loud. It’s not that I was glad that Jim was dead, but he was. And because of the chaos of his death I had a chance to break out of my crystallized and hardened patterns of predictability, to crack the calcified static of my life. In the rubble of Jim’s illness and death, I had a chance to walk into the next stage of my life with a new perspective. Some people never have, or take, this chance; instead they become frozen into who they are, what they think, how they act.” |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed