I’m so thrilled to share the cover for my new novel, If Not the Whole Truth, publishing with Margin Key, which will land in bookstores and on Amazon on September 10, 2024. Paperback and eBook. The proof has been proofed, the send button on the changes has been pushed. Don’t you think this cover is epic? I’m so lucky to work with Stephanie Shafer on the design of both the cover and the lovely interior. The paper rips on the printed book cover look so real, you want to run your finger over them. I can hardly wait for you to meet Connie Borders. An Irvington (Indianapolis) brat, her life gets ripped up again and again, but she never loses her verve. This book was eight years in the writing and research, and a bit more nipping and tucking as it tried to find its own way in the world. I had a blast checking out the fashion, food, music, (‘cause Connie dresses for the occasion, slaves away in restaurant kitchens, has a steady soundtrack) and language of both the late 1960s era and the final 2022 chapter. Over eight drafts (the early ones oh so rough!), characters appeared, then disappeared. Some characters were killed off and then came back to life. Others killed with no return. Adventures had and then deleted. A million comma uses considered. In an early draft, a beta reader pointed out that for an era of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, I had plenty of drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but not enough sex – so I had to fix that. And by fixing that I discovered not only joy, but some very dark places familiar to many women. And then, there were all the books and old newspaper articles (mainstream and underground) about politics, war, and protests. Rich in content and tone, their stories made my story so much better. But more importantly, writing the book deepened my grasp of what was really going down in the activist years of the late 1960s era (as if anyone ever really knows what going down) and how it’s tied to what’s going down today. It reinvigorated my own activism, not on a global scale, but on my community and neighborhood level, because that’s where my scope of influence lies. I hope it will do the same for you, or at least start some interesting conversations. Because, you know, we think life changes, but does it really? The core of this book illuminates how the basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. PS Are you a typography wonk like me? Here’s the names of the fonts on the cover: Wavespired by Invasi Studio and Manic by TYPEHEIST. And inside, everything runs along smoothly, unlike poor Connie’s explorations, in classic, beautiful Baskerville.

2 Comments

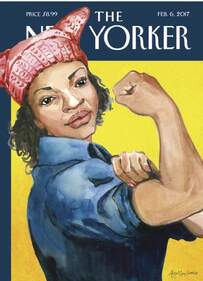

In the wayback machine, almost ten years ago, the Library Journal gave a super nice review to my memoir, Leave the Dogs at Home, thanks to the efforts of Indiana University Press to get the book on the Journal's radar. Wellllll, fast forward to the now. My new novel, If Not the Whole Truth, is being published by my own micro-publishing house, Margin Key, and all the thousands of details about book design and promotions are up to little 'ol me. Some of this is fun. Like getting to choose my book designer and being involved in the creative process of cover design and book composition. I love typography, I love art, but the responsibility for the correctness of the files and all the details of publishing sits squarely in my lap, and it's a little scary. Also in my lap is the effort to get advance reviews from recognizable places to encourage sales. Places like the Library Journal. From my perspective, a review from them is important because that's how you get your book in front of librarians. It's how your book gets ordered by libraries. As an aside, did you know the Library Journal was founded in 1876 by Melvil Dewey? There's no guarantee they'll review the novel; they review several hundred each month. I can’t find any info about how one is notified if the book is reviewed. And, if I'm lucky enough to get a review, it could be positive and/or negative, and they will recommend for or against purchase. But I have faith in my book, and I want to hear what the Library Journal thinks this round. (I’m pleased to report Kirkus Reviews said this: “Historically rich, with … searing contemporary relevance. OUR VERDICT: GET IT.”) First, you've got to ask months and months in advance. My novel is not coming out until September and it's already a little late for asking for reviews from the LJ. But this is where I'm at because even though we started on the book final final final edit and design in early March, I didn't have an electronic file to send until last week. (Be watching for a cover reveal coming soon!) Getting the file to the LJ is an exercise in hyper-detailed instruction following. Have to request to set up an account. Then, if approved, download a spreadsheet that must be filled in just so and not structurally modified in anyway. Then the book PDF and the completed spreadsheet have to be uploaded on a special webpage in just the right order. Then, you wait to hear if the files were “successfully processed into our book room.” I uploaded on Sunday, got my success email this afternoon. All of that is due to my careful planning and execution. I knocked, the door opened. And closed. And now If Not the Whole Truth is on its own behind the mysterious Library Journal doors. Will it survive?  Slow briny sweat dripped into Sharon’s eye, determined and persistent. She wiped it away with the red faded bandana soggy from an afternoon of sweat and snot and stuffed it back into her equally sodden rear pocket. Behind her a tidy, curated garden unpocked with pioneering grasses and wandering upstarts. Before her, a browsy mass of mildewy coneflower and yellowing milkweed in a spiky undergrowth of orange cosmos being invaded by snow-on-the-mountain that was aquiver with honeybees, three different kinds of wasps, and who knows what kind of flies. Beyond that a vegetable garden with Italian zucchinis and purple-podded green beans that somehow grew from pinky finger size to giant overnight in the late summer humidity. As she took a step into the tangle, Sharon’s phone dinged: the half-hour alert for the evening abortion ban protest. But right there beside her foot was a young, enterprising poison ivy plant. She plucked a large violet leaf, folded it over, and wrapped it around the stem to block the urushiol oils from touching her and yanked out the plant. A risky maneuver, but it had worked before. A few steps beyond, a bristly patch of nut grass. She bent under the tall, floppy bee balm to pull out the long dangling rhizome roots, and then pruned the bee balm for another round of late flowering. Her phone dinged again. Now, only fifteen minutes to get downtown. Sharon took three giant steps out of the flower bed and ran to the mud room at the back of the house. She stripped off her bug-sprayed outfit and flew into the shower to soap off any chiggers that had wiggled through to bury into her tender parts like the sense of dissatisfaction that had sparked the women’s movement on suburban patios back in the 1960s. She shouldn’t have dawdled in the garden, now she is late. Prompt by habit, late isn’t a word that comes up in Sharon’s life often, and while she stepped into her jeans, it blossomed in her mind like a spot of period blood on a sanitary napkin. Late was a word of horror in her youth, in the days before she got birth control under control, before getting her tubes tied. Late terrorizes women for half their lives. The checking of the calendar, a paper calendar for her back then. How many days late? Am I late or did I skip? Hand tentatively hovering over the belly. Month in and month out. From the kitchen, the final alert dinged on Sharon’s phone. She shoved it in her bag and rushed to the garage. The tires on her bike needed air. She watched the gauge on the hand pump steadily climb to eighty pounds pressure, like the pressure that built up in those suburban women of old, before Roe v. Wade. As Betty Friedan put it in her book, The Feminine Mystique, it was a pressure, a strange stirring, a yearning arising from a long buried, unspoken problem: “Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—‘Is this all?’” Sharon didn’t read The Feminine Mystique when it came out; she was too young to notice it and her mother, who had worked her whole life, never mentioned it. In fact, Sharon hadn’t ever read the book until last month because for years she arrogantly considered herself the embodiment of feminism. First a braless, hippie chick who felt liberated enough to erroneously believe that she could align her periods with the phases of the moon for birth control. Even more so as a single mom who managed to pull off a decent career. But lately, with the whole feminism movement beating a retreat as the be-fruitful-and-multiply tradwives in aprons became the new radical counterculture, Sharon sensed her style of feminism was out of touch, even as an escort at Planned Parenthood and a member of NOW. The first hill into town was a ball-breaker. Sharon pointed her bike toward the rise and pedaled in low gear. Fast, then slow teetering at the top, finally growing steady and catching her breath in front of the green bungalow with the familiar Ruth Bader Ginsburg decal on the door. “Women belong in all places where decisions are being made,” read the decal next to an image of Ginsburg in her lace collar. Sharon threw Ginsburg a dirty look. The judge knew Roe v. Wade was headed for attack; she should have stepped aside early. She’d gambled with the rights of women and lost. Tomorrow, Indiana reinstates its abortion ban. Coasting down the hill, wind cooling her over-heated face, Sharon was furious that she had to leave her garden in a weedy mess for an abortion ban protest. Outraged that the rights won by those historically, histrionically, desperate women have been snatched away. The first of many rights in the shredder, perversely in the name of freedom. She sped up and coasted through a stop sign so she could get up the next hill. It’s not like women’s rights hadn’t been stolen before. She’d found the history, thanks to Professor Google and the New York Times archives. During WWII women had flooded into jobs and college slots. The Rosie Riveters that everyone knows about made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. But others held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. They filled the classes of universities. They were confident and independent. They made good money and had future careers. At the end of the war in September of 1945, all of that was stripped away and handed to returning soldiers in a false fear that the Great Depression would return. In just three months a million women were “freed” from their jobs. Soon it would be half of all working women. The rest took on grunt pink-collar jobs. Future doctors were recycled into high school biology teachers. The first-in-her-class Harvard grad Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. The wartime economic engine shifted gears and the Golden Age of Capitalism was ushered in by career housewives retrained to shop. It was a career of discontentment that left them feeling empty and invisible. A boxed-in brain-death boredom that beget a desperation so red hot that not even a martini with a twist could douse it. A desperation as broad and deep as the disenfranchisement that boosted Trump into the Oval Office and Sharon’s news feed. The Feminine Mystique sold three million copies in three years. Read in between making the Jello salad and folding the laundry, it roused women into following the lead of the civil rights movement, but often without women of color. They didn’t storm the Capitol, but they marched. They wrote books, started Ms. magazine. They ran for office, spurred equal pay and rights legislation. It’s because of them that all women can have credit cards and houses in their own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was because of these rabble-rousers that all women have access to birth control. And, for a brief shining moment, the right to end unwanted pregnancy. Then in 1981, things started tumbling backwards. Just as Paula Hawkins of Florida was the first woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate without following a husband or father in the job, and Sandra Day O’Connor became the first woman on the Supreme Court, the idea that equality was a step down for women began to gain traction. And abortion rights became political bait. If the weather had been cooler and the hats hadn’t been dumped as racist and transphobic five years ago, Sharon might have worn her pink knit pussyhat from the Women’s March in D.C. at the beginning of Trump’s term. What an exhilarating day that was even if the new administration couldn’t care less. But it wasn’t useless. Like a good soaking rain stimulates growth in a garden, it stirred hundreds of women to run for office and tens of thousands to register to vote. The same ones that were voting for abortion rights state-by-state. Sadly, the sparsely right-to-choose gatherings on the courthouse lawn in little radical Bloomington and the ignored demonstrations at the Statehouse in Indianapolis never moved the needle in MAGA, cornfield-ruled Indiana that refused to put abortion on the ballot. But she went anyway. Sharon darted up an alley and onto the courthouse square. It was empty of protesters. Not even one waving a sign at passing cars. Locking her bike to the rack, she scanned the grounds for her friends and cocked her head to listen for protest chants, but there were none. She took the steps two at a time, toward the young organizer by the empty stage in the niggardly shade of a tall, skinny ginkgo tree. Sure the protest had taken off down the street without her, Sharon asked, “Which way did the march go? I need to catch up.” “March? There’s no march. It was a vigil.” “Vigil. That’s a hopeless perspective.” Sharon took off her bike helmet and shook out her hair. “Where is everyone?” “Gone.” “What do you mean, gone?” “You are late. Almost two hours.” The woman tapped her smartwatch. “That damned calendar app.” Sharon pulled out her phone and glared at it. “The time dial-ly thing is hard to use.” “I wondered where you were, hoped you weren’t sick or something. I know people texted you.” To Sharon’s chagrin, she saw a pile of texts from her protest friends. “Crap, I remember, I turned off text notifications. Got sick of texts sidetracking me and forgot to switch it back.” The woman gave her a poor-confused-old-lady look while brushing away an evening mosquito from her taut-skinned arm. Her phone buzzed. “I’ve got to take this; it’s a reporter from Indianapolis.” “Thanks for being here in time,” Sharon said as she turned away, longing for her days of unwandering focus. Of taut skin and thick hair. Days that felt like good change was in the air. This abortion thing made her want to move out of the state. But no matter where she might go, stifling attitudes toward women would go with her. They were woven into the culture, like racism. And for hard-working women of color, like the one following up with the reporter, it’s a double whammy. Suddenly thirsty for a stiff drink, Sharon jaywalked across the street, and found an empty solo seat at the bar crowded with young hipsters, many sporting tattoos on their firm skin and most with lots of thick hair including a couple of man buns and a braided beard. The bartender, busy performing a focused mixologist show—muddling, high arcs of pouring, over-the-head shaking—didn’t even glance Sharon’s way. She looked over the slim menu of craft cocktails with craftier prices, knowing that if she ever got the bartender’s attention she’d better be ready to order. Beyond her, with the studied look of a scientist, he measured dry gin, sweet vermouth, and Campari into a glass beaker of ice, stirred the brilliant red liquid with a long, twisted handled spoon, and strained it over a perfect square of ice in a round rocks glass. Sharon waved as he looked up after twisting a swath of orange peel into the classic Italian Negroni, miraculously catching his eye. She pointed at the drink and then to herself, nodding. He gave her a thumbs up. Negroni. One of those words that seemed like it is racial but isn’t. Like niggardly. Sharon looked around the bar. A white crowd. One that might be called privileged. Like her. Her Ancestry DNA test had shown she was Scottish through and through. She had hoped for a more diverse set of inputs, but it wasn’t to be. And her immigrant story is so old no one in her family remembers it. Born humbly, she never thought herself privileged until the woke movement awoke her to the simple enduring benefits of having pale skin, even wrinkled. The Negroni show encore was underway in front of her. The bartender measured and poured. He dramatically stirred, twisted, and placed the gorgeous ruby-red drink in front of her with a flirty flourish. She did her best eye-twinkle back and took a sip of the bitter cocktail. So appropriate for the day. On the TV hanging above the bar, news flashed of Trump’s lead in the polls and his likely indictment in Georgia for election meddling. And with it evidence of a new wave of feminism. The prosecuting district attorney with the lyrical Swahili name, Fani Taifa Willis, daughter of a Black Panther, taking on the biggest-baddest in front of the whole country. Sharon raised her glass to the steady-gazing prosecutor. “Here’s to you, Madam DA.” A few weeks ago, Sharon had been blown away by another woman with the mantle of a different power wrapped around her. The keynote speaker at the Bloomington Women’s History Month Luncheon, the resonating Manón Voice of Indianapolis, seemed made of the same passionate and poetic magnificence as Martin Luther King and Fred Hampton, but with a hip-hop sensibility. As the booze softened her brain, Sharon realized that women of color caught her eye more often than white women as they took their rightful place on the stage of the big world, the one beyond her fussy garden. They are fascinating. They stir her. She listens to Kamala Harris speeches. Takes the painful Smarter in Seconds lessons of Blair Imani on Instagram. Has Isabel Allende’s new novel, The Wind Knows My Name, on her bedstand. Loved Michelle Yeoh in Everything Everywhere All at Once. Inhales Amanda Gorman in each Vogue-y dress of the moment and has this stanza of her inaugural poem on the refrigerator: And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside She jostled her drink around the posh ice cube. Truth be told, she is a women-of-color groupie. But, after a lifetime of being surrounded by white, this influx of color is, well, colorful. What idiot wouldn’t be fascinated? But, she had read enough online to know that this, her riveted groupieness, is racist. That locked white eyes upon non-whiteness is an unwanted heavy weight for others to carry. Draining the last watered-down sip of the Negroni, she paid in cash with a small tip for the bartender—who never gave her a second look, or even a bill—and took her infinitely flawed and obviously unfascinating self home. *Rosie the Riveter reimagined as a woman of color, illustrated by artist Abigail Gray Swartz, graced the New Yorker February 6, 2017 issue, paying homage to the past, present and future of the feminist movement. As we dip into winter and all of its reflectiveness, I have the pleasure of being a featured reader along with local Bloomington author Molly Gleeson. Put it on your calendar! A excerpt from Leave the Dogs at Home and my new upcoming book If Not the Whole Truth.

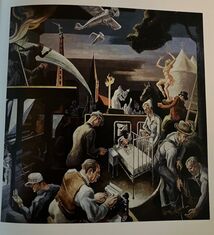

First Sunday Prose Reading and Open Mic presented by Writers Guild at Bloomington WHEN: December 3, 2023, 3:00 pm – 5:00 pm WHERE: Morgenstern's Bookstore and Cafe, 849 S. Automall Rd., Bloomington  I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.

IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—Is this all?’” Today is the birthday of Betty Friedan, born in Peoria, Illinois (1921). Her thoughts, like the one above, put forth in 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, roused women into action for equality, challenging the widely shared belief that fulfillment had only one definition for American women: housewife-mother. Friedan was right about the depth and breadth of women's dissatisfaction. The book sold three million copies in three years. Women had been discouraged from working during the depression to give men jobs. But during WWII they flooded into jobs and college slots vacated by men gone to fight. They were independent. They made good money. They had future careers. They made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. They held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. But all that was lost upon the return of soldiers when the fear of another depression forced women out. It was promoted as the patriotic thing to do, but it decimated women’s lives as they were systematically relegated to pink-collar jobs in law, medicine and business or no jobs at all. Everybody knows how the brilliant Ruth Bader Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. But what I remember was my mother’s bitterness over being shunned by other women for working in our family flower shop. And the woman who married my stepfather after my mother died: she was forced out of medical school to make room for returning veterans and had to accept a career as a high school biology teacher when she wanted to be a doctor. But by the 1960s, the nearly psychotic and bored white women of the suburbs (yes, the same women courted by today’s politicians) tossed aside Tupperware, frozen dinners, and tranquilizers to put their racist, Bardot-draped, shoulders into righting the listing ship of women’s equality. They wrote books, marched in the streets, launched legislation, started magazines, ran for office. And strategically excluded women of color, just like the old suffrage days. That oft-scorned movement put women in congress, allowed us to have birth control pills and the right to terminate unwanted pregnancy, credit and houses in our own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was the second wave of feminism. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 stipulates that women receive the same pay as men for the same work. We're still working on that. And working on even allowing women to hold equal jobs. Stifling attitudes toward women are woven into our culture, like racism. And for women of color, it’s a double whammy. I have deeply pondered my own racism. From my late teens on, I did everything I could think of to reject racism. But recently, I was trashed on social media as a racist. At first, I protested. Not ME! But then I realized my trasher was right. I’m racist. I can’t help but be racist. And I have to own up to it because it helps me see my privilege, helps me understand the anger of those who look at me in disgust. This has led me to believe I am also riddled with bias against women, even though I am one. Even though I experienced decades of sexist slap-downs, forged radical non-Hollywood relationships with men, clawed my way as a single mother to fairly respectable positions, and pride myself on my feminist views. I can’t help it. It’s buried in me. Like racism, it’s part of my foundation. I was taught. By my family, my teachers, my bosses, my friends. By the lack of female authors, artists, scholars, or innovators available from which to learn. I can fool myself—like I did in the 1980’s, thinking I was no longer a racist because I forgot a Black friend’s color—that I’m not sexist because I have tried hard to unlearn what I was taught. It’s hard to excavate my biases. Almost impossible to see them. They lie hidden in my dark, irrepressible judgement of women who have chosen paths I deem inadequate—dissing Melania Trump’s plastic-surgery-modeling-rich-guy route when I should just try walking a mile in her ambitious, sky-high stilettos. They seep into my own language, that I must vigilantly correct—calling Joe Biden, Biden; but calling Kamala Harris, Kamala. Beyond me, out in the larger world, the third wave of feminism is blossoming. I Googled “feminist activists 2020,” and first up came a link to an October 2020 post on Mashable, “6 feminist activists to follow on social media.” Right away, I’m heartened. The women are all colors, shapes, sizes, ages, and religions. They are probably racist and sexist too, but I’m following them. Closely. And hoping, as this young woman points the way for us all: "...And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside..." --Amanda Gorman  People whine, or more modernly "whinge," about new words. About the new ways of using old words. They want to nail down English, make it hold still. Like a dead language, like Latin. But English is alive, recklessly sprouting new words for old things, new words that meant old things but with a new twist, old words used new ways, and new words for new things. I used to be deep in the whirlpool of new words, so close that I was one with it. I was plugged-in when plugged-in was added to the dictionary. A new word would appear in my mind seamlessly as it shot across the tongues of my friends and the pages of books and newspapers. Far out. Fab. Groovy. Outta sight. Righteous. Bummer. Gimmie some skin. Hang loose. Ecosystems. Whole systems. Spaceship Earth. Zero population. Wild edibles. Amerika. Dig it. Later, I was there in my little suit and scarf when Materiel Management booted out the Purchasing Department and Human Resources took over the Personnel Office. I ran spritely beside adware, subfolder, brain dump, microbrew, the n-word, and biodiversity. I was hot when chill out was a thing. But somehow, slowly, almost imperceptibly, some words started outpacing me. A new word for stealing, “gank,” (as in “you ganked my X-Box”) came and went without me. Polyamorous slipped by me unnoticed but woo-woo didn’t. Then one day I was shocked to discover that garden ecosystems were old hat, replaced by the swankier permaculture. Gen Xer’s had axed that old-school talk and broadened the idea. By renaming it, they claimed the concept, took it away from the hippies-turned-Boomers. I resisted. I didn’t want to use that new, pretentious word. Then I realized this is how a person grows old. One step at a time out of sync as the words dance and mutate until they have all rushed ahead and left you behind with a curly old lady perm and frumpy clothes. No longer yogurt, sourdough, and sauerkraut; it’s wild fermentation. It’s not you are what you eat, it’s the microbiome. New and redefined words swirl up like mosquitoes on a hot summer night from the internet, the news, movies, and conversations. Has it always been this fast? Have words always been this fleet-footed but we didn’t know how to measure? “Are you going to temp that?” The Oxford English Dictionary (which keeps track of a thousand years of English and some 600,000 current and obsolete words) has added more than 4,000 new words since the beginning of 2019. And I think they are behind. I know I am. It took me forever to fully understand the ridiculously simple word, “meme.” And “litigate” challenges me as it populates the news, mirroring the contentiousness of our society, as in this sentence from the New York Times: “Racism is litigated over and over again when another video depicting another atrocity comes to light.” Litigate in my mind has always meant to decide in a court of law. But now its archaic meaning, to dispute, has been re-embraced. Who started that? Bitchface. Clapback. Nothingburger. Shade. Throwing shade. Meme. Tropes. Dog whistle. Salty. Troll. Dox. The singular They. Woke. Lynching. White fragility. Infodemic. Hashtag. They rush toward me, not just as new words but as signs of seismic changes. The world shifting beneath me like the proverbial quicksand from which Lassie had to rescue Timmy on television back in my childhood.  Channeling Christo while painting where the water heater used to be. Channeling Christo while painting where the water heater used to be. The cheerful slant of spring sunlight is coming through the kitchen window. It plays across the covered mound of bread dough rising in my well-scratched, old Pyrex glass mixing bowl. The rest of the afternoon will be punctuated with kneading, punching down, and patiently waiting for rises. By oiled black cast iron pans. The aroma of baking bread will fill the house as the sun sets. This sudden bout of bread making follows a week of industry. Painting, mending, cleaning, pruning, and weeding with great determination and gusto. Now I’m trying to resuscitate my blog. You might think it’s corona virus hunkering. But it’s not. This is my emergence. Not hunkering at all. The tackling of chores put off after months of hunkering to do another rewrite of my new book. This version, 3.5, required eight months of hunkering. Since I started this novel in June of 2015 (a month before Leave the Dogs at Home was published by IU Press, a year before I had surgery and radiation for breast cancer) there have been several manuscript hunkerings. The first draft was finished in a daze from a concussion after being knocked silly by a distracted driver in a left-turning car bowled me over as I was crossing the street on an October evening in 2016. I thought that draft was magnificent, at least while I was writing it. Later I realized, thanks to some honest readers, that it was anything but. Still, all but one reader thought idea had merit; it was worth the slash and burn of total revision. Worth the hunkering. I have loved the book. Hated it. I have put it aside. Gave up writing all together for a bit. I have taken travel breaks. To Istanbul and Athens. To Russia, China, and Europe. To Paris twice with my daughter. Paused to help my sister when she had a couple of strokes. Sagged while saying goodbye to my dogs Lila and Diggity, my cat Cirrus. Put my all of the rest of my life aside to work on it. Gave up all of my other writing to write it. Papered my office with diagrams of the story arc and post-it note character pathways. Lived with winding stacks of books and thick files. Renewed subscriptions to newspaper archives many times. I’m not complaining. I like myself best when I’m writing. When I’m a crazy woman up until three in the morning, wandering, writing, researching, muttering, rewriting. My head full of the story, the images, the music, the passion. Dreaming about it. Eating it. Breathing it. Writing it. My new book is a story about the time that made this time. It's story of a determined young woman finding personal truth in the upheaval of the hippie antiwar and counterculture movement. Years later in a 2022 America fraught with extreme social and political tension, her hard-learned stance puts her life on the line.

There were just a few short years when people truly believed they were going to change things for the better. Believed in their music as a social binder. Together they could stop the war, make abortions legal; pull communities out of poverty. bring real equality to our society. There was a real sense of optimism and hope that the country, the world, was on the cusp of a new system of love, trust, and brotherhood. We talked about eco systems, and you are what you eat. But we all know that was a pipe dream. Life went on pretty much as it had before. A few things changed, but the big picture did not. The hippies cut their hair and got mortgages. And today, we are so far, far away from the ideals of equality and peoplehood, from the Woodstock Nation. So polarized that we can’t even agree to hunker down together. It makes me want to hunker down. Except, that's exactly the wrong reaction. I'm going to get out there, and listen, and let my voice be heard where it can be heard, in my own town and neighborhood. It's like Fred Hampton once said, we have to deal "with what reality is, whether we like it or not."  It was a helluva thunderstorm last night. I was lost in a good book about perfume and murder in Paris, in my PJs nested in my comfy bed when the rain began pelting the window and the thunder booms started echoing. I snuggled in, pulling up my favorite light green feather comforter, and read on, feeling safe and happy in the pool of the soft light from the lamp by the bed, the iPhone plugged in on the night stand, and my dog Lila snoring at the end of the bed. Then there was a crashing sound. I hate crashing sounds. No good has ever come from a crashing sound. This one was loud and dull, came several times, and then stopped. Tree limbs on the deck or on the car? Blown over something somewhere now a broken mess? Before I knew it, I was out of bed, heading down the stairs, dreading what I might find. I stopped at the base of stairway to listen and think about from what direction the sound had come. I turned on the dining room lights and the front porch light, opened the door, walked out, looking for storm damage. That’s when I heard the footsteps on the deck. And a muffled voice. My front porch is connected to a small deck on one side of the house. There’s a latched gate between two. Footsteps on the deck meant that someone had unlatched the gate and was just around the corner. My heart raced. I ran inside, locking the door behind me. Then the dull crashing sound came again. A thumping really. At the double glass French doors that open onto the deck. Without thinking, I switched on the deck light. And there on the other side was someone. Right on the other side of the glass. Standing under the eave out of the rain. A thin young woman. Straight blond hair. A pink jacket with fancy leather stitching on both sides. A phone to her ear. Looking directly at me. “Get out of here,” I shouted. She had no response, as if the sound didn’t travel through the glass. She threw herself against the door and tried to open it. My mind flooded with the memories of a woman who walked in my unlocked front door one Saturday afternoon in Cincinnati some 30 years ago. Walked in as if she owned the place. Said she was being pursued by murderers. Refused to leave. We tussled. She was strong and scary, broke away from me and ran up the stairs to my bedroom, laid on my bed. Vomited. Ranting the whole time. I finally was able to get on the phone in the kitchen to call the police while Emily (who was just a teenager) kept track of her. I was worried that murderers would come barging in the front door any time to kill her. I’d seen that happen before in Chicago some 50 years ago during another house break in. But they didn’t and cops came, got her, knew her. She was off her meds, she had done this before. “You should keep your door locked they told me.” So I do, mostly. But not always. But lately, since my car has been rummaged through a couple times over the past year, I’ve started checking the doors and the car to be sure they are locked before I go to bed. I miss the days when I didn’t need to lock the door. There’s a imprudent part of me that thinks that since I have a dog, people won’t come in. Crazy people don’t care about dogs though. And Lila would be the first to run from a crazy person. In fact, she was upstairs sleeping while this current crazy person was right on the other side of the glass, slamming her body into it. I should have called 911 right then. But I forgot about doing that and instead got my sturdy Alaskan Diamond Willow stick from where it leans against a cabinet in the living room. I held it up with both hands like baseball bat, showing her that I’d be glad to wallop her on the head with it, and made a fierce face. “Get!” I shouted, pointing toward the little gate and the front porch. “Get out of here. Go home.” She looked at me blandly. Again as if she couldn’t hear or see me. Behind her, a wide bolt of lightning split the night sky and lingered vibrating forever, driving electricity into the earth. I threatened her with my stick again. A smirk crept across her face and struck fear me. “I’ve got a crazy here,” I heard her say into her phone. Then, looking directly at me through the glass door, she spoke into the phone in a tiny voice, “Help me, help me, help me.” My body tingled with fear, my mind throbbed with the surreality of this. The two of us standing body to body with glass between us. I was so vulnerable and visible. I had to get away and be safe, out of the light. I turned off the deck and dining rooms lights, put the stick on the breakfast bar, and ran upstairs to call 911, But I forgot to turn off the light in the stairway where a newly installed LED super bright floodlight bulb illuminates the entire world. She could still see in, and she resumed throwing her weight against the glass door. Over and over. What was happening, what did the person look like, did I know her, had I ever seen her before, what was my phone and address, asked the woman who answered the 911 call. I replied quickly and nervously, my heart in my throat, from the landing, afraid to make the turn to the downstairs where she could see me, the blazing light still on and me too thick to turn it off. “She’s banging on the door hard,” I said over and over, nearly matching the rhythm of the thumping. There are police nearby I was told. Don’t go downstairs. Don’t open the door. Stay on the phone with me until the police get there. The slamming stopped. I crept down the steps and saw her turn away from the door. Will she leave before the cops come? Will I seem like a crazy old lady when they arrive? Then I heard her open the screen door on the front porch and try the knob of the front door. Thank god I had relocked the door. I could hear her say into the phone, “It’s locked.” On my phone, the 911 operator says the police are out front right now, but don’t open the door until I tell you. I open the blinds of the front door, and there she is. The screen door open, her hand on the knob trying again and again to open it. We look at each other through the glass. Then she turns. A tall uniformed man is behind her. I tell the operator and open the door. Immediately the cop tells me to close the door. I see a woman officer with a blond ponytail come up on the porch through the blinds. The operator asks me if I am okay and we hang up. There’s a big, loud conversation on the porch that I can only hear part of, mostly what the cops say. Do you know where you are? No. You are not even close to there. Show me your ID. A real ID. A debt card is not a real ID. The woman who lives is 75 years old, do you have a friend that’s 75 years old? You are causing yourself trouble. Is that your roommate on the phone? Let me talk. Eventually, a wet young policeman came in through the deck door to write down the facts in a narrow lined notebook. I turned on the light in the dining room so he can see to write and I tell him my tale. Another pokes his head in to see if I wanted to press trespassing charges. When I said no, he disappears. Then the question of do I want her to be arrested if she ever comes back. My mind refuses to decide, the question seems so weird. I ask the officer for a recommendation, and he says that’s what he would do. So I say yes. I asked him if I did the right thing, calling 911. He says yes, and leaves. Meanwhile out on the porch, things are de-escalating. I open the front door. The tall officer, and the woman officer are on either side of the young woman. He tells me they have called a cab for her and asks if it’s okay for them wait on the porch out of the rain for it to come. And could I close the door, close the blinds, but leave on the porch light. So I do. I’m inside alone, my bare feet damp from the water that’s been left on the rugs, standing there with all my cells on alert. I sure as heck can’t go back to bed yet. I hear the cop ask the young woman if she wants to sit down. Peering through the side of the blinds on the door, I see her on the porch swing. “Thank you, thank you,’ she says in an exhausted voice. “I know. I just want to go home.” Time ticks. I hear the officer ask if he should call her roommate who was on the phone. And her reply that that wasn’t her roommate, and his simple “Oh.” Then would she like him to give her a ride home. I hear her say yes, if he’s allowed to do that. I hear their footsteps on the porch steps. Crack the blind. See the dark police car drive away. It’s so quiet. The storm has subsided. Lila comes downstairs to smell the police footprints. I turn out the porch light. Somehow, I feel left out. Uncomfortably invisible. Funny, since that was what I'd wanted to be earlier. Then I feel guilty. If I’d had my wits about me, I could have calmed her down and driven her home myself. But, I guess calling the police, and them doing it, was a better idea. I pee, go back to bed, and can’t sleep. I’m supposed to get up early to go to a symposium at IU in the morning, but it’s 2 a.m. now. The image of the wet, lost young woman on my porch saying into her phone, “Help me, help me, help me” resurfaces. How she didn't seem drunk, she was eerily alert. And the physical memory of my fear. I was scared of her. A young, skinny, lost, wet woman. Afraid that if I opened the door, she’d be wild inside, that she’d hurt me, a not-even close-thank-you-very-much-to-a-75-year-old-woman. I feel weak. I feel stupid. I scold myself for not making good decisions quickly, for my lack of focus. Digging into big fat slices of humble pie. The silly Diamond Willow stick. Why did I agree to the trespassing thing? What would have happened if she'd been a more fierce intruder? Could someone come through those glass doors? Then worse, I think of what might have happened to her if I’d been successful in shooing her off the deck, the porch, out into the storm. Of never found Lauren Spierer, the wee hours video image of her walking on bare feet in the alley. And murdered Crystal Grubb, her head bashed in, body found in the corn field. Of Hannah Wilson, snatched from town, her body dumped out on Plum Creek Road. Would I have read in tomorrow’s paper about of the body of this young woman found in the little creek that runs by my house? I wondered if she’d been dark-skinned, black-haired instead of being a cute light-skinned woman in stylish clothes would she have been given the gracious ride home by the police? Would the situation de-escalated? It was long time before I went to sleep. And when I awoke, I felt uselessly haunted by this incident. Unresolved and resolved at the same time. I could have shaken off this whole thing by going to the symposium, but I blew it off. |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed