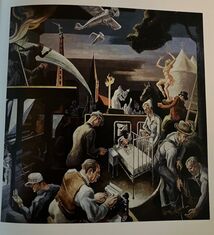

I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.

4 Comments

IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE IMAGE: IAN MOORE / MASHABLE “The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night—she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question—Is this all?’” Today is the birthday of Betty Friedan, born in Peoria, Illinois (1921). Her thoughts, like the one above, put forth in 1963 book, The Feminine Mystique, roused women into action for equality, challenging the widely shared belief that fulfillment had only one definition for American women: housewife-mother. Friedan was right about the depth and breadth of women's dissatisfaction. The book sold three million copies in three years. Women had been discouraged from working during the depression to give men jobs. But during WWII they flooded into jobs and college slots vacated by men gone to fight. They were independent. They made good money. They had future careers. They made airplanes, ships, munitions, and tanks. They held technical and scientific jobs for the first time. But all that was lost upon the return of soldiers when the fear of another depression forced women out. It was promoted as the patriotic thing to do, but it decimated women’s lives as they were systematically relegated to pink-collar jobs in law, medicine and business or no jobs at all. Everybody knows how the brilliant Ruth Bader Ginsburg couldn’t get a job as a lawyer. But what I remember was my mother’s bitterness over being shunned by other women for working in our family flower shop. And the woman who married my stepfather after my mother died: she was forced out of medical school to make room for returning veterans and had to accept a career as a high school biology teacher when she wanted to be a doctor. But by the 1960s, the nearly psychotic and bored white women of the suburbs (yes, the same women courted by today’s politicians) tossed aside Tupperware, frozen dinners, and tranquilizers to put their racist, Bardot-draped, shoulders into righting the listing ship of women’s equality. They wrote books, marched in the streets, launched legislation, started magazines, ran for office. And strategically excluded women of color, just like the old suffrage days. That oft-scorned movement put women in congress, allowed us to have birth control pills and the right to terminate unwanted pregnancy, credit and houses in our own names, admission to top-drawer universities, and careers beyond menial labor. It was the second wave of feminism. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 stipulates that women receive the same pay as men for the same work. We're still working on that. And working on even allowing women to hold equal jobs. Stifling attitudes toward women are woven into our culture, like racism. And for women of color, it’s a double whammy. I have deeply pondered my own racism. From my late teens on, I did everything I could think of to reject racism. But recently, I was trashed on social media as a racist. At first, I protested. Not ME! But then I realized my trasher was right. I’m racist. I can’t help but be racist. And I have to own up to it because it helps me see my privilege, helps me understand the anger of those who look at me in disgust. This has led me to believe I am also riddled with bias against women, even though I am one. Even though I experienced decades of sexist slap-downs, forged radical non-Hollywood relationships with men, clawed my way as a single mother to fairly respectable positions, and pride myself on my feminist views. I can’t help it. It’s buried in me. Like racism, it’s part of my foundation. I was taught. By my family, my teachers, my bosses, my friends. By the lack of female authors, artists, scholars, or innovators available from which to learn. I can fool myself—like I did in the 1980’s, thinking I was no longer a racist because I forgot a Black friend’s color—that I’m not sexist because I have tried hard to unlearn what I was taught. It’s hard to excavate my biases. Almost impossible to see them. They lie hidden in my dark, irrepressible judgement of women who have chosen paths I deem inadequate—dissing Melania Trump’s plastic-surgery-modeling-rich-guy route when I should just try walking a mile in her ambitious, sky-high stilettos. They seep into my own language, that I must vigilantly correct—calling Joe Biden, Biden; but calling Kamala Harris, Kamala. Beyond me, out in the larger world, the third wave of feminism is blossoming. I Googled “feminist activists 2020,” and first up came a link to an October 2020 post on Mashable, “6 feminist activists to follow on social media.” Right away, I’m heartened. The women are all colors, shapes, sizes, ages, and religions. They are probably racist and sexist too, but I’m following them. Closely. And hoping, as this young woman points the way for us all: "...And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us but what stands before us We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside..." --Amanda Gorman  People whine, or more modernly "whinge," about new words. About the new ways of using old words. They want to nail down English, make it hold still. Like a dead language, like Latin. But English is alive, recklessly sprouting new words for old things, new words that meant old things but with a new twist, old words used new ways, and new words for new things. I used to be deep in the whirlpool of new words, so close that I was one with it. I was plugged-in when plugged-in was added to the dictionary. A new word would appear in my mind seamlessly as it shot across the tongues of my friends and the pages of books and newspapers. Far out. Fab. Groovy. Outta sight. Righteous. Bummer. Gimmie some skin. Hang loose. Ecosystems. Whole systems. Spaceship Earth. Zero population. Wild edibles. Amerika. Dig it. Later, I was there in my little suit and scarf when Materiel Management booted out the Purchasing Department and Human Resources took over the Personnel Office. I ran spritely beside adware, subfolder, brain dump, microbrew, the n-word, and biodiversity. I was hot when chill out was a thing. But somehow, slowly, almost imperceptibly, some words started outpacing me. A new word for stealing, “gank,” (as in “you ganked my X-Box”) came and went without me. Polyamorous slipped by me unnoticed but woo-woo didn’t. Then one day I was shocked to discover that garden ecosystems were old hat, replaced by the swankier permaculture. Gen Xer’s had axed that old-school talk and broadened the idea. By renaming it, they claimed the concept, took it away from the hippies-turned-Boomers. I resisted. I didn’t want to use that new, pretentious word. Then I realized this is how a person grows old. One step at a time out of sync as the words dance and mutate until they have all rushed ahead and left you behind with a curly old lady perm and frumpy clothes. No longer yogurt, sourdough, and sauerkraut; it’s wild fermentation. It’s not you are what you eat, it’s the microbiome. New and redefined words swirl up like mosquitoes on a hot summer night from the internet, the news, movies, and conversations. Has it always been this fast? Have words always been this fleet-footed but we didn’t know how to measure? “Are you going to temp that?” The Oxford English Dictionary (which keeps track of a thousand years of English and some 600,000 current and obsolete words) has added more than 4,000 new words since the beginning of 2019. And I think they are behind. I know I am. It took me forever to fully understand the ridiculously simple word, “meme.” And “litigate” challenges me as it populates the news, mirroring the contentiousness of our society, as in this sentence from the New York Times: “Racism is litigated over and over again when another video depicting another atrocity comes to light.” Litigate in my mind has always meant to decide in a court of law. But now its archaic meaning, to dispute, has been re-embraced. Who started that? Bitchface. Clapback. Nothingburger. Shade. Throwing shade. Meme. Tropes. Dog whistle. Salty. Troll. Dox. The singular They. Woke. Lynching. White fragility. Infodemic. Hashtag. They rush toward me, not just as new words but as signs of seismic changes. The world shifting beneath me like the proverbial quicksand from which Lassie had to rescue Timmy on television back in my childhood. |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed