In the wayback machine, almost ten years ago, the Library Journal gave a super nice review to my memoir, Leave the Dogs at Home, thanks to the efforts of Indiana University Press to get the book on the Journal's radar. Wellllll, fast forward to the now. My new novel, If Not the Whole Truth, is being published by my own micro-publishing house, Margin Key, and all the thousands of details about book design and promotions are up to little 'ol me. Some of this is fun. Like getting to choose my book designer and being involved in the creative process of cover design and book composition. I love typography, I love art, but the responsibility for the correctness of the files and all the details of publishing sits squarely in my lap, and it's a little scary. Also in my lap is the effort to get advance reviews from recognizable places to encourage sales. Places like the Library Journal. From my perspective, a review from them is important because that's how you get your book in front of librarians. It's how your book gets ordered by libraries. As an aside, did you know the Library Journal was founded in 1876 by Melvil Dewey? There's no guarantee they'll review the novel; they review several hundred each month. I can’t find any info about how one is notified if the book is reviewed. And, if I'm lucky enough to get a review, it could be positive and/or negative, and they will recommend for or against purchase. But I have faith in my book, and I want to hear what the Library Journal thinks this round. (I’m pleased to report Kirkus Reviews said this: “Historically rich, with … searing contemporary relevance. OUR VERDICT: GET IT.”) First, you've got to ask months and months in advance. My novel is not coming out until September and it's already a little late for asking for reviews from the LJ. But this is where I'm at because even though we started on the book final final final edit and design in early March, I didn't have an electronic file to send until last week. (Be watching for a cover reveal coming soon!) Getting the file to the LJ is an exercise in hyper-detailed instruction following. Have to request to set up an account. Then, if approved, download a spreadsheet that must be filled in just so and not structurally modified in anyway. Then the book PDF and the completed spreadsheet have to be uploaded on a special webpage in just the right order. Then, you wait to hear if the files were “successfully processed into our book room.” I uploaded on Sunday, got my success email this afternoon. All of that is due to my careful planning and execution. I knocked, the door opened. And closed. And now If Not the Whole Truth is on its own behind the mysterious Library Journal doors. Will it survive?

0 Comments

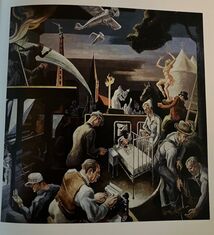

I used to think I understood truth. It was the simple, direct, honest representation of fact. But, truth be told, truth and facts are slippery. I'm not talking about Orwellian doublethink alt-facts that are outright lies, or truths all twisted up with bullshit. I'm talking about facts without context, without a full understanding of circumstances, intent, or perspective. Do we ever really know the whole story about anything? Truth can be downright hard to fix in place. It changes right before your very eyes, shifting in the light of bias and history. Like a fawn hidden in the tall grasses by the doe, truth's origins, awkward connections, and political or moral inconveniences are folded and tucked away. The tender parts that complicate, but illuminate, understanding can be hard to find. And who has the time anyway? If it doesn’t fit in a headline, a 30-second news bite, or a tweet, it’s just too much. In my college freshman philosophy course I learned that a table, which seems a fact we could all agree upon, is not the same table for all of us. The table you see is not the same table I see. Because you bring different ideas to the table than I do. You see it in a different light. It's Bertrand Russell's argument that reality is distinct from its appearance. It’s not even the same table for me each time I look at it. And even though we might agree that the table looks smooth, it’s all rough hills and valleys under a magnifying glass. Under a powerful microscope it's xylem, phloem and ray vascular tissue. All truth, but all different. Depending on perspective. The whole story never completely revealed. This played out in my town, Bloomington, Indiana, in a lecture hall on the campus of Indiana University. Well, what used to be a lecture hall until it became too controversial. Toward the front of the hall are two, 12-foot-high Thomas Hart Benton paintings, striking in their undulating forms and bold color. One is titled Indiana Puts Her Trust in Thought. But no one ever talks about it. The other one, titled Parks, the Circus, the Klan, the Press, sets people on fire. It’s one of 11 sections of a mural that details the complex, and oft dark yet also oft hopeful, cultural history of Indiana. There’s a lot going on in the painting (as in all Benton paintings): airplanes, a water hose putting out a fire in a skyscraper, a striker throwing a rock, a circus act, a tree being planted. And it specifically puts in brashly applied egg tempera paint the story of the 1928 Pulitzer Prize winning take-down coverage of the Klan by the now long-defunct Indianapolis Times. That story is at the center of the painting. And it gets people’s attention, as Benton intended. In the background there’s a clump of tiny nightmarish, white-sheeted, hooded KKK figures with an American flag rallying like madmen by a burning cross and a church steeple. They are eclipsed by a press photographer, a reporter pecking at a typewriter, and worker at a printing press in the foreground. To the side a White nurse cares for both a Black child and a White child, equality seemingly secured. But that wasn't what some students thought as they sat dwarfed in the room by the eternally frightening KKK silently shrieking in supersize. They didn't know the story of painting, and if they did, they didn’t want to sit held captive next to the image of the ghastly Klan figures every day in class. From their perspective, all they could see and feel was racism and oppression, not the hope of Benton’s story that the worst of the worst could lose their grip on society. Especially since the Klan never did completely die out. Especially since racism and oppression are still alive and well everywhere today. So, students circulated petitions to have the painting removed or covered. The painting survived, but now the room no longer hosts classes. It sits mostly empty, door locked, entry by appointment only. Benton had important facts that he wanted remembered, but the pressure of modern sensitivities shouted more loudly than an old, dated painting done by someone that’s only relevant to a few. Sadly, I have Klan history in my family, most White, multi-generational Hoosiers do because the Klan once ruled the state. And I grew up in the Indianapolis neighborhood where the KKK Grand Dragon (ugh, what a title) once ruled from a big, white-pillared, plantation-like mansion. But today I live in Bloomington. It’s a blue oasis in the bright red state of Indiana that loves license-less open gun carry, abortion bans, marijuana bans, book bans, cigarette smoking (around 30%!), and deep-fried tenderloins, brownies, and cheese on a stick. Bloomington’s libtard acknowledgement of systematic racism is not popular out in the corn and soybean fields. I miss visiting the painting and its power of that takedown, but I try to hold on to hope that this country can turn things around. Making things better is the theme of much of my life. Many moons ago I was a student in that classroom, and the painting filled me with pride that conservative Indiana had once stuck it to racism, bribery, corruption, and murder that went all the way to the mayor of Indianapolis and the governor of the state. There's a direct, indirect, straight, wavy line that links the daring of today's civil unrest to the upheaval of the 1960's and early 1970s that lured me so many years ago. It was a time fraught with truths that could only be partially seen, and so much has been forgotten about what really went down. Good and bad. Still, it was a time that I thought would change everything for the better. Equality across the board. Voting rights, equal pay, women’s right to make her own decisions about abortion and birth control, to control her own life and money. Civil rights. Housing rights. The acknowledgement of the contributions people of color and women made in history. All of that is being chipped away today. We think life changes, but does it really? The basic struggle for power versus equity rolls over again and again. So caught up in the arrogance of each era and generation, we hardly notice that the tune to which we dance to is on repeat. Maybe with a different rhythm, or some reverb, but it’s the same. And if we don’t understand how each moment is tied to the past, tied to our basic flaws as humans, we have no possible hope of moving ahead. No hope of unlocking doors that prevent us from walking around the table so we can see it from every angle.  Virginia always takes me by surprise. I’ll be rearranging my NetFlix queue or doing some other essential but non-essential thing - cooking, dusting, or paying bills - and a green flash of Virginia darts in. The blue, hazy vistas. The open high mountain pastures. Fat yellow, black and white striped monarch butterfly caterpillars munching on milk weed. White two-story farmhouses with green roofs and wrap-around porches. The images elbow each other for room in my mind. I stop, pull back from whatever I'm doing, and let it all flow over me. I invite in those ancient folded Appalachian ridges that stretch from Newfoundland to Alabama and pull up little slices of Virginia luck. Pale pink spring cherry blossom petals blanketing the ground, up to my ankles. A sign in the window of the H&H Cash Store in Monterey, next to a poster for maple syrup and buckwheat flour: If we don’t have it, you don’t need it. The August heat hammering down any thought of moving quickly. Thousands of Arbogasts in the wide Shenandoah Valley and the steeps and flats of Highland County. Tiny Willie’s Pit BBQ hole-in-the-wall BBQ in Staunton that’s not there anymore.

And then, a few days later on Tuesday, April 26 at 7 p.m., after I have checked in and found my long-lusted-after seat in a rocking chair on the second story porch at the Highland Inn in Monterey, high up in the "little Switzerland" of Virginia, I am lucky enough to do a reading at the public library. It was in Highland County that I began to understand that in the debris of Jim’s death was a remarkable gift, really a rare chance to remake myself --the core of Leave the Dogs at Home’s story: Here's an excerpt: White picket fences announced McDowell, which was really just a few houses along the road. It was easy to find the old house—it was the only brick house in town. It was a Hull family house built in the 1800s that had served as a Stonewall Jackson headquarters, a Civil War hospital, a hotel, a stagecoach stop, and now a museum. I left the girls in the Element under a lone tree several blocks away, every possible window open, water dish filled to the brim, and calculated I had an hour before the sun moved from behind the tree to beat down on them. A stray breeze moved through the thick air. Maybe it was slightly less hot here. My elderly cousin was waiting for me upstairs at a heavy wooden table in a room lined with genealogy books. The slight scent of mildew tickled my nose. An air conditioner cranked noisily in the window. My shorts and T-shirt seemed disrespectful next to his white pressed shirt and brown suit and tie. He listened to me recite my lineage, nodding his head at each generation. Elizabeth and Michael. Elisabeth and David. Katherine and Enos. Isabele and Sanford. Cordelia and Enos. Pearl and Straud. Maxine and Elmore. “Yes, I know your family,” he said. “And I know where the old house is.” I unfolded a map and scooted it across to him. He ran his thin, smooth fingers over the web of back roads. “The old house is here,” he said, tapping at the map with his index finger. “In the field behind a newer house. As you drive around this curve you can just see it. It’s before the road turns to gravel and goes up the mountain. It was in Arbogast hands until a few years ago, but they had to sell.” Three hours later I pulled the truck over onto a small grassy shoulder in the curve of road next to a flock of sheep, the dogs whining to chase the herd. I thought this spot might be where my cousin had pointed to on the map. There was an old house set back far away. I couldn’t really see. The air undulated in the broiling sun. And then it hit me. It didn’t matter if this was the house or not. What mattered was how Michael had broken free from the restraints and traditions of the old ways to find a new way in a new land. He had left the old wars and took on new ones. While others cried and whined over being duped by the Soul Traders, he served his time and made his dream happen. Who knows what misery and horror he might have seen, being the only survivor of his German family, who may have been wasted by typhoid fever or mowed down in war. But Michael built a better life on the disaster of their deaths. As surely as he mourned them, he lived proudly and made Arbogast a name that rings with honor across the Shenandoah Valley. My Jim and career disasters seemed so shallow in comparison and my bleak grief over the loss of the former me so indulgent. But one thing was for sure: my life was getting better. I wasn’t headed for just a different life, but a better one and a better me. One that would not be here if Jim were alive. And it was time to be grateful and unabashed about living it. This is verboten thinking. Widows and left-behind lovers are never supposed to say this. We’re supposed to say that our relationships and marriages were perfect. You were crazy in love. It’s like half of you is gone, He was everything to me. Once your main squeeze kicks the bucket, the union, no matter how complicated or imperfect, becomes sacrosanct. The dead one golden and wonderful, the one left behind without a reason to go on. All the bad times must fall away, and only the good times can remain. We are allowed to stumble onward, bravely. We are allowed to heal and learn to enjoy life again. We are allowed to love again. But we are not supposed admit that life is better after a lover’s death. I needed to write about this, but I didn’t want to. People would think it was cathartic, therapy writing, a cleansing. A way for me to process my emotions. But I was doing just fine processing. I didn’t even think I was forging new ground. All I was doing was walking a path walked by many but unspoken of, and these important things needed to be said out loud. It’s not that I was glad that Jim was dead, but he was. And because of the chaos of his death I had a chance to break out of my crystallized and hardened patterns of predictability, to crack the calcified static of my life. In the rubble of Jim’s illness and death, I had a chance to walk into the next stage of my life with a new perspective. Some people never have, or take, this chance; instead they become frozen into who they are, what they think, how they act.”  Eating ice cream on Daddy's birthday, a family tradition of oh so long ago! Eating ice cream on Daddy's birthday, a family tradition of oh so long ago! Tuesday was Arbogast feast day. I was so busy, I forgot to celebrate. I almost always forget. You'd think I'd remember, because the 21st is also my father's birthday, a memory rich with vats of homemade ice cream and plates heavy with thick-sliced tomatoes. oh well. Instead I will give a nod to my 5th great grandfather, Michael who, with his wife Elizabeth, started up the Arbogast clan that arose from Virginia. Michael immigrated from Cologne, Germany where he was born in 1734. He arrived on the Speedwell in Philadelphia at age 17, parents and siblings all dead, and threaded his way through the big mountains west of the Shenandoah Valley to Highland County in 1758. These days, Arbogast is known as a "good valley name" and the graveyards are full of Arbogast tombstones, unlike Indiana. Immigrants from Germany, England and Ireland (plus a few folks wooed from Pennsylvania) were the ones who felled the trees in Virginia to made way for the farms, and to pay off their passage. He was naturalized in 1770, patented 130 acres there in 1773 and added more acreage over the years. He married a natural born Virginian and fathered two rarely noted daughters and seven oft-noted sons (several of whom served in the American Revolution). He died at age 79. In his will, he left his wife "one-third possession of at the time of my decease for and during her natural life time and her to keep possession of the dwelling house where in I live during the said period of her life and the adjoining to said house and all the under of following articles: to-wit, her bed and furniture, one pot, one baskin, one dish, two plates, two spoons, one fleish fork, one laddle, one kettle, one coffee pot, two teacups and saucers, one set of knives and forks, lisc (?) tin cups, two chairs, one large chest, one spinning wheel, one wool wheel, one pair wool cards, one pair cotton cards, the table in the house, all her books, her saddle and bridle, one tin bucket, three coolers for milk, two head sheep, two of my best milk cows, one horse creature, of not less value than fifteen pounds currant money, all her clothes, and the mulatto girl named Nancy." I hope things worked out okay for Nancy. My 4th great grandfather, David Arbogast. and his brother Michael, and "their heirs from them" were excluded. Maybe they had already received their shares when emigrating on to the east, or maybe there just wasn't enough room in Virginia for all of those big Arbogast personalities. Michael moved over the mountain to establish Arbovale, now part of West Virginia. David moved to Indiana, leaving his twin brother behind. David, who with his wife Elizabeth had five sons and four daughters, died at 109 years of age in Andersonville, in Posey Township - about two hours away in the northwest corner of Franklin County. Originally known as Ceylon, was laid out in 1837 by Fletcher Tevis, and renamed in 1849 after Thomas Anderson, a tavern owner. David was living in Virginia when he was 49, and it looks like all the kids moved with him, so the next 50 years surely were interesting. |

Inside

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed